Face Value

Writer Larissa Dubecki Published The Age on 17 April 2008.

For sale. Typeface. ‘Bisque’. Brand new, made in Melbourne, one of a kind. Will deliver anywhere in world. Apply eBay.

Stephen Banham loves typefaces. The 38-year-old graphic designer is the kind of fellow whose idea of fun is writing down every example of typography in the kilometre between Flinders Street and Latrobe Street. For Banham and a worldwide clique he calls ‘type nuts’, typefaces – also known as fonts – aren’t just a utilitarian tool to deliver a message. They’re a work of art. They are a thing of beauty embedded in a social message and as worthy of critical consideration as architecture, painting and fashion design.

In a world-first experiment that floats a typeface on the open market, Banham, pictured left, is auctioning his newly minted Bisque typeface on eBay. From today until the auction ends on April 27 — World Graphic Design Day and, serendipitously, Banham’s 39th birthday — Bisque will take its chances among the flotsam of the online auction house. “It started off almost as a joke in that we were looking at the typeface wondering how we would market it. We laughed, then we looked at each other and thought, ‘Why not?’,” he says of the decision he made with Bisque’s co-creator Niels Oeltjen.

The auction has the veneer of a novelty, and in some ways it is an in-joke for graphic designers. In others it’s a serious experiment in creating an alternative to the usual methods of selling fonts. Usually a corporate client such as Telstra will commission an exclusive font, with an attendant fee in the tens of thousands of dollars. Alternatively, graphic designers create a font and license it online to anyone who pays a small fee. “Bisque is a fusion of the two, feeding into the idea that the typeface hasn’t been designed under a brief but you can buy the exclusive rights of it by auction. I wouldn’t have a clue how it’s going to go,” says Banham, who anticipates the likely buyers of Bisque to be a magazine or branding company.

Some might remember Banham from a typeface movement he started at the turn of the century. Death to Helvetica was the result of dissatisfaction with the corporate world’s embrace of the sans serif font known as Helvetica. It wasn’t the font itself with which Banham had a problem; rather the way it became the de-facto brand of business and government, its cane-toad like appropriation of public space swamping font diversity.

To someone who sees typeface as a potent form of social expression, the proliferation of Helvetica was disturbing.

“It was really a call to graphic designers to look at the effect graphic design has on the visual environment because we should be at least partially responsible for that,” he says. “I’ve always thought it odd that you open up the newspaper and have a column on theatre, and a column on art, and a column on architecture even but you’ll never ever have a column about graphic design or typography because it fails to engage the public.”

Banham was at one stage destined for the ranks of advertisers more concerned with selling a product than thinking about the effect their work has on the visual environment. He trained as an advertising art director at RMIT but lasted just one afternoon at an agency in late 1980s — “it was horrible, power suits and attitude” — before his zeal for the written letter led him to found graphic design company Letterbox in 1991.

The Flinders Lane-based company aims to create a culture around its work, augmenting commercial projects with their own brief to engage the broader public in the language of graphic design and typography. Some of the more novel — and in some instances, apocryphal — obsessions with typeface are captured in one of Letterbox’s publications, Fancy. Along with the famous Arthur Stace, the Sydney-sider who for 35 years spread his religious message by chalking “Eternity” in copperplate script on city streets, there’s a man who spent 24 years collecting examples of naturally occurring letters and numbers on butterfly wings, and office cleaners known as “the on/off movement” who use the lights of darkened office buildings to create messages.

There’s also the tale of Peg Entwhistle, a failed actress who threw herself off the Hollywood sign in 1932. “She climbed the upper case H and threw herself off, becoming the only person who’s killed themselves using typography,” Banham says.

The ubiquity of computers towards the late twentieth century saw an explosion of font design, from an estimated 1500 typefaces worldwide in the early 1980s to about 60,000 in 1996. The past seven years have seen that number climb again into the hundreds of thousands.

As with any piece of design, typography is subject to whims of fashion and can personify a time and place — thus Helvetica, says Banham, is inextricably linked to political conservatism. Gill sans is a classic English typeface, while the Americans tend to go for big sans serifs such as news gothic — “they’re very chunky and come from an advertising base”.

Australia, conversely, doesn’t have a defining style of font, meaning that possibly our streets and buildings exhibit more typefaces than Europe — “although the only way to find out is to map city blocks in other countries, which would be such fun to do”. Banham, who also lectures in typography at RMIT, has made “seven or eight” typefaces before but Bisque is his favourite and most complex to date.

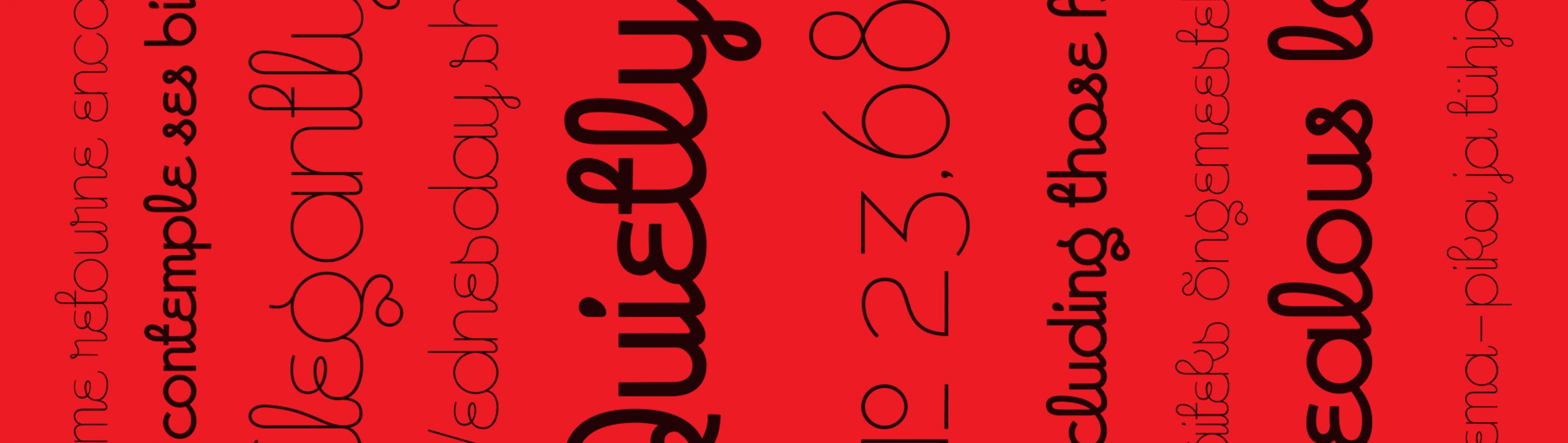

An undeniably young font that screams “look at me”, Bisque’s capital E, Q and W sport a flirty loop that’s counteracted by the austerity of the L, M and N. In design-speak, it “features a staggering array of ligatures, contextual alternates and kerning pairs”, which means that when run together in lower case it creates pleasant whirls and strange intersections. “I like its fluency,” Banham says. “It’s extremely engaging yet readable. It has an informality about it yet it’s quite unique.” Creating a typeface requires an enormous investment of resources and time, he says; Bisque took almost eight months to finish. “In some ways the creation of typeface is arcane,” he says. “It’s coined as ‘the invisible art’ and it’s often taken for granted, and yet we couldn’t do without it.”