What Lies Beneath

Writer Ray Edgar Published The Age newspaper on 8 January 2011.

A playful art project turns Point Cook footpaths into stories of the past, present and future.

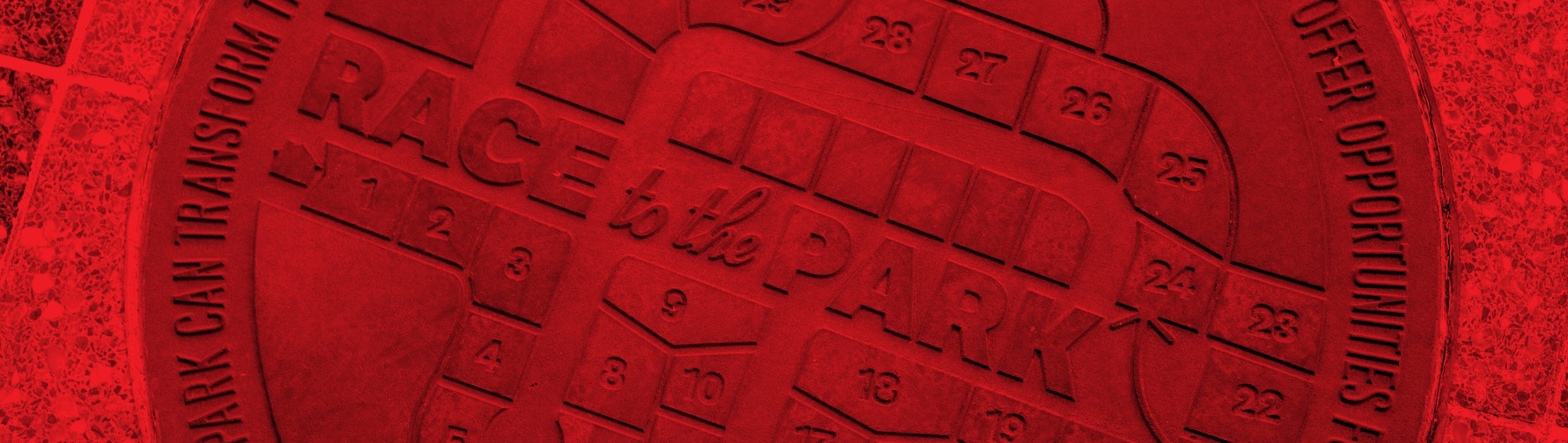

Bring Mary back ‘any which way you can’ was the order Thomas Chirnside gave his brother Andrew. It was 1852 and Thomas paid a high price for the return of his Scottish beloved. Mary did make the long journey to Australia, but as Andrew’s wife. The poignant triangular relationship at the Chirnsides’ vast estates at Werribee and Point Cook is one of eight compelling stories that celebrate the people of the Point Cook community through public art. Against the flashy facades and cluttered services along Point Cook’s Main Street, designer Stephen Banham and artist Christine Eid have placed eight finely crafted manhole covers into the footpath at each pedestrian crossing. This prosaic, industrial form is not the obvious medium around which one rallies civic pride and populist appeal. Yet it’s the allusion to public works that makes the manhole cover a fitting reminder that the community owns them. They carry the additional advantage of being low maintenance. But these are far from utilitarian objects. They travel through time.

The Circular Project demonstrates how public art can be delivered through effective design solutions. Forget the familiar monuments of bombastic bronze statuary and indulgent sculptures. “The last thing we wanted to do was just put some other bloody great thing into this crowded environment,” Banham says of the Main Street shopping precinct. “There’s a zillion things going on in the consumer area. So we thought why not put [our public art] flat to the ground. “We wanted the plates to be a quiet discovery but, at the same time we wanted them to be quite beautiful and complex,” Banham says of his first public-art project. “As with any type-based project, it was about trying to find an appropriate typeface for the content.”

A typographer working primarily with digital technology, Banham particularly enjoyed the opportunity to tell the older stories through type derived from an era when fonts were hand-drawn and more ornate. “Some are quite playful and others are more serious.” From the Boonwurrung and Woiwurrung-speaking people’s hunter-gatherer habitation to the pastoral era of the Chirnsides, the rising importance of aircraft to the area, to the passion for communal gardens, the Circular Project is a reminder to visitors and, especially, Point Cook’s newest settlers, of the area’s rich history. Conceived through six months of community consultation, the plates carry with them games, stories, and – despite the material’s Dickensian connotations – even an online component. Like a cast-iron board game, the manhole cover art offers activities such as mazes, identilication charts for spotting birds, planes and plants, and downloadable animated Hick books. It’s the appeal to children that is particularly important.

Five years ago Point Cook’s town centre was still paddocks with sheep and chaff. Now according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, it`s the fastest growing area in Victoria and the fourth fastest in Australia. In the past year, the city of Wyndham cites an increase of nine new households a day It’s the future generations that the Circular Project particularly addresses. While juicy historical facts such as winning Mary’s heart and (the poisoning of the Chirnsides’ racehorse Newminster (who, despite the dose, went on to win the first Caulfield Cup of 1879) were cast iron gold (to mix metals), Banham and Eid were keen to look to the future. As well as interviews with the historical society and librarians, school students were approached to gauge their hopes and dreams for their new suburb. With the permission of Carranballac P-9 Colleges Boardwalk School’s headmaster, Banham and Eid interviewed the students. “We got kids into groups of two and they worked together to draw a picture of their hopes and aspirations for what Point Cook would be like in the future,” Banham explains. “While some went for the space machines, others went for a low-fi, grassroots kind of thing. It was all about the community and peace and vegetation and the environment. It was amazing. The idea of gardens was a common concern.” And so a plate depicting plants and gardens was cast.

One of the goals of public art is to bring the works out of the museum and into the community But does consultation take the democratisation of art to an extreme degree? While not advocating community engagement for every project, Donald Williams, director of art consultants Global Art Projects who commissioned Banham and Eid, says one of its benefits is community ownership and less vandalism. “It sounds a bit of a cliche but they feel proud of it.” Far from being some alien object with little connection to its surroundings, let alone its community the Circular Project avoids the other common problem of public art. If sculpture is the stuff we bump into, public art is the stuff that often gets in our way. Discreetly embedded into the landscape, the manholes serve another practical purpose. “When people walk along a street they often look down so that’s also a good thing. It will be seen.” The project is testimony to the changing approach to public art. “Rarely do you see ‘plonk art’ as we used to call it,” Williams says . “The antiquated notion of the artist being the single genius who can impose their uber vision and make some grand artistic statement is becoming increasingly redundant,” Banham says. “It’s not about statements. It’s not about the big exclamation mark, it’s about the big question mark. It’s about posing questions and telling stories. The idea behind good design and engaging art is to listen as well as produce.”