Australian Graphic Design B Sides: Philip Brophy

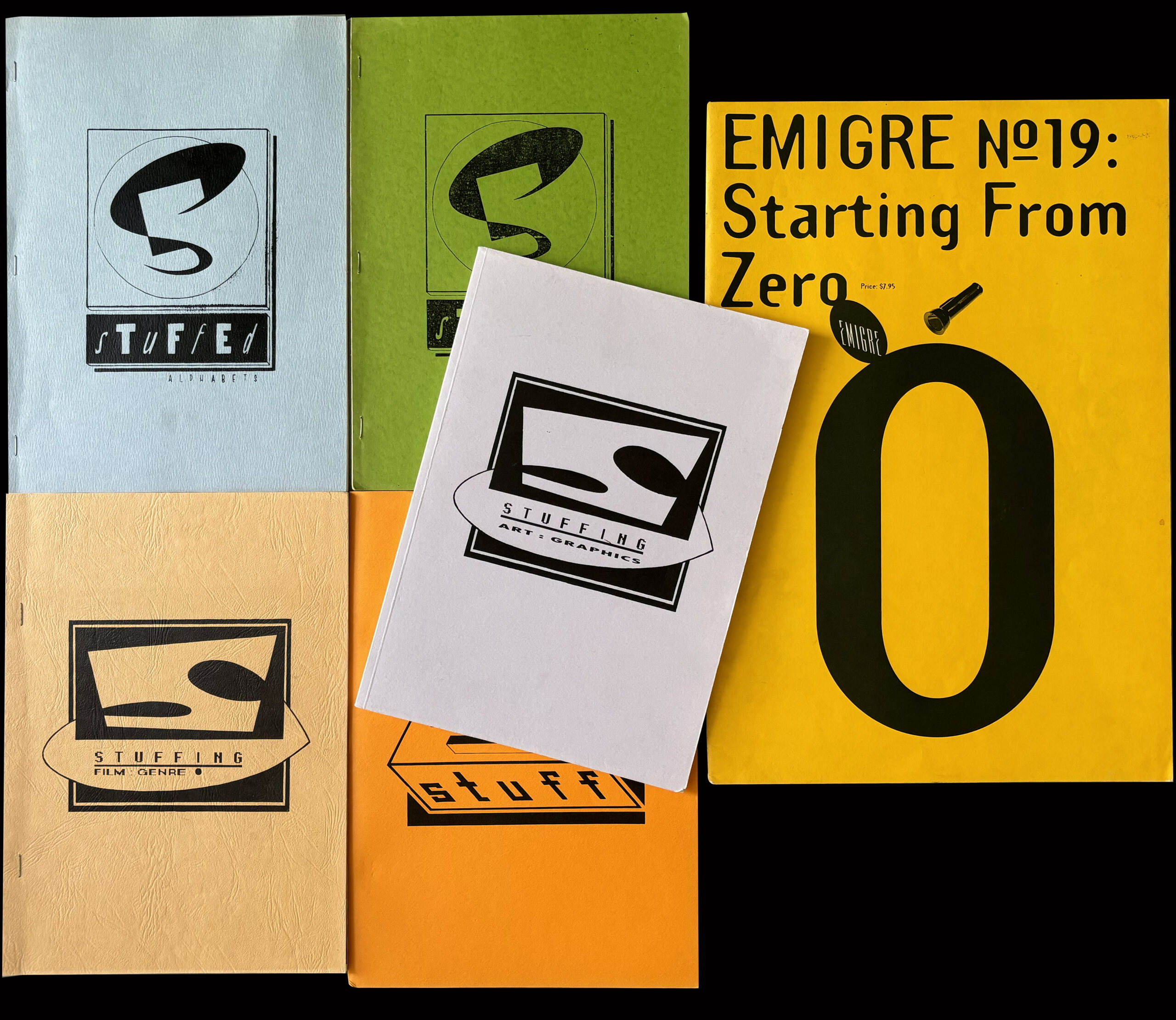

I recall the first time I read something that suggested that graphic design had its own intrinsic heartbeat. It was 1990. Unlikely titled Stuffing, the publication was unassuming – simply photocopied in black and white and stapled. But the texts offered a rare cultural reading of graphic design, making connections into the worlds of music, art, film and pop culture. And to my absolute delight this gem had been produced in Melbourne.

The significance of Stuffing was reinforced a year later when one of its essays by Keith Robertson, Starting from Zero, ended up as the primary text in Issue 19 of Emigré (1991). The originator of the series (Stuffed, Stuffing and ReStuff) is Philip Brophy – a figure whose creative interests experience span art, music, film and writing amongst others. Writing forcefully from the edges of graphic design at a time when critique was rare, makes him one of the more interesting and unapologetic observers from this period. I sat down with Philip to discuss the series and a whole lot more.

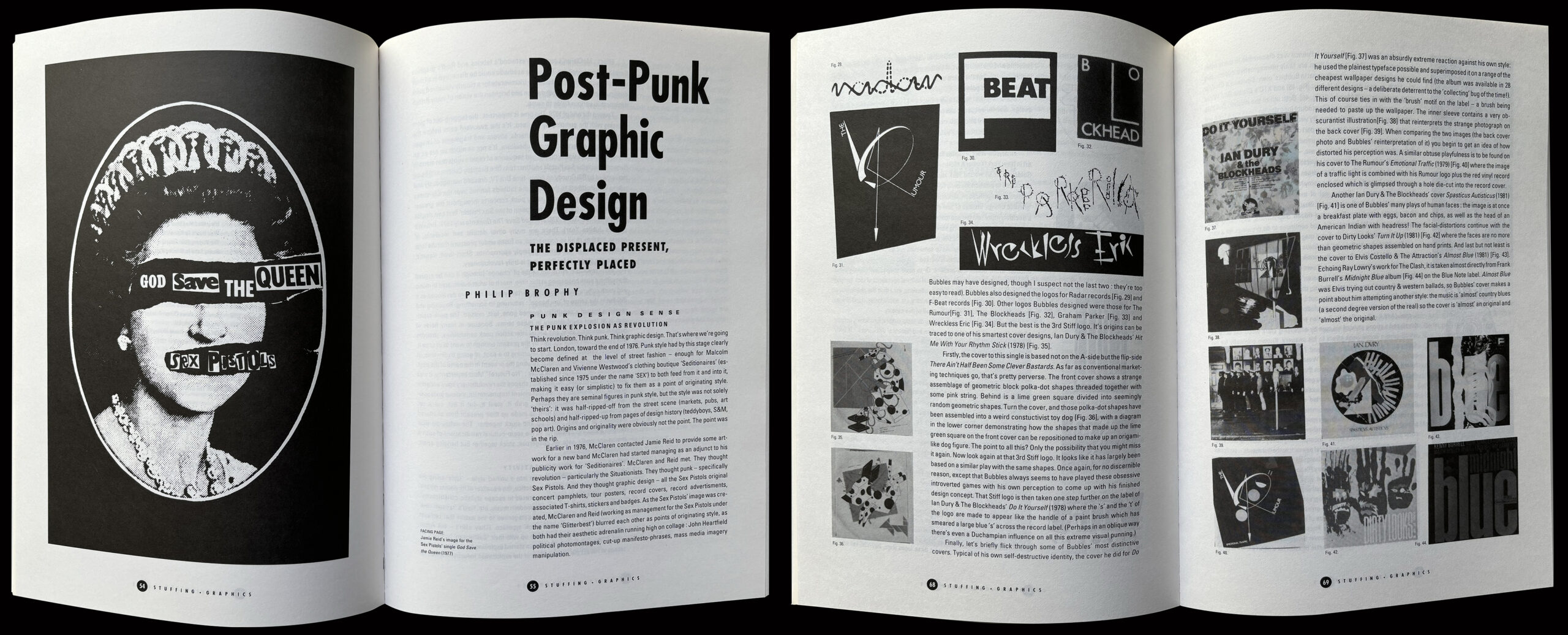

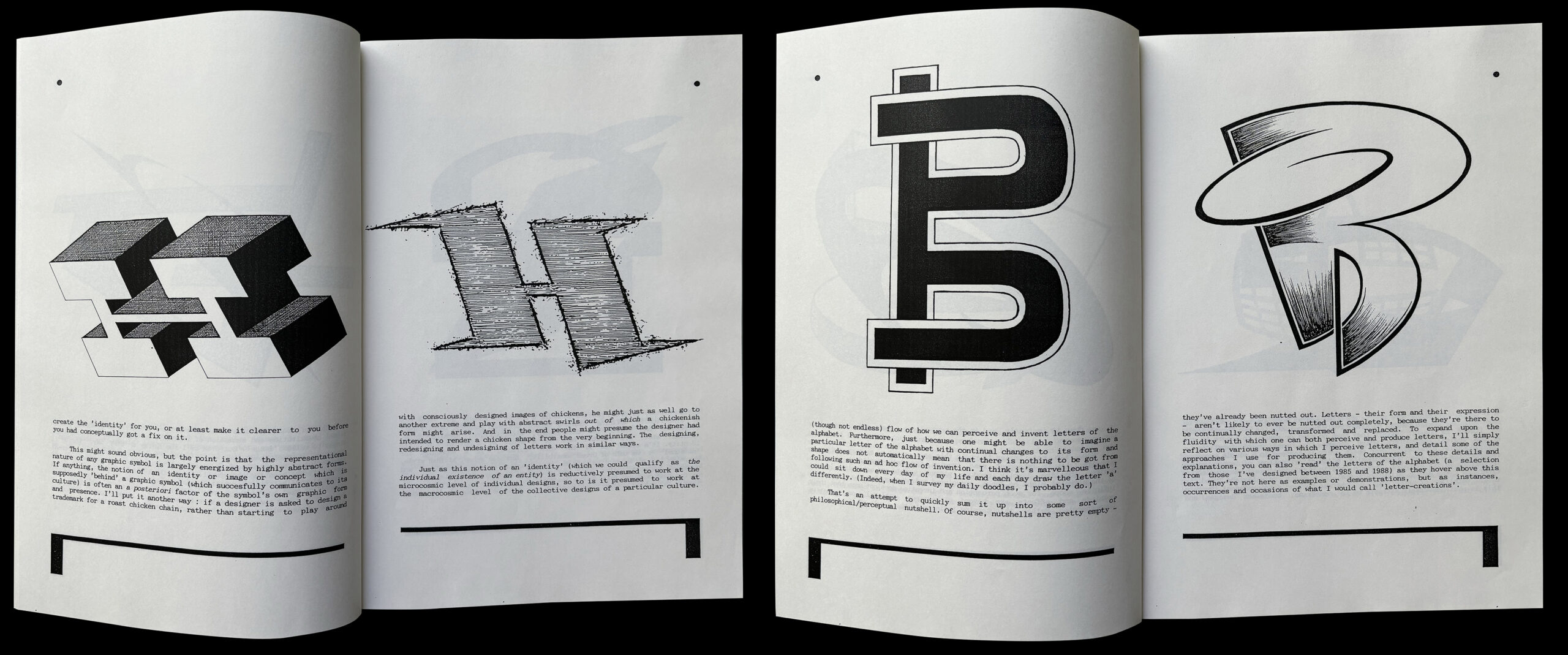

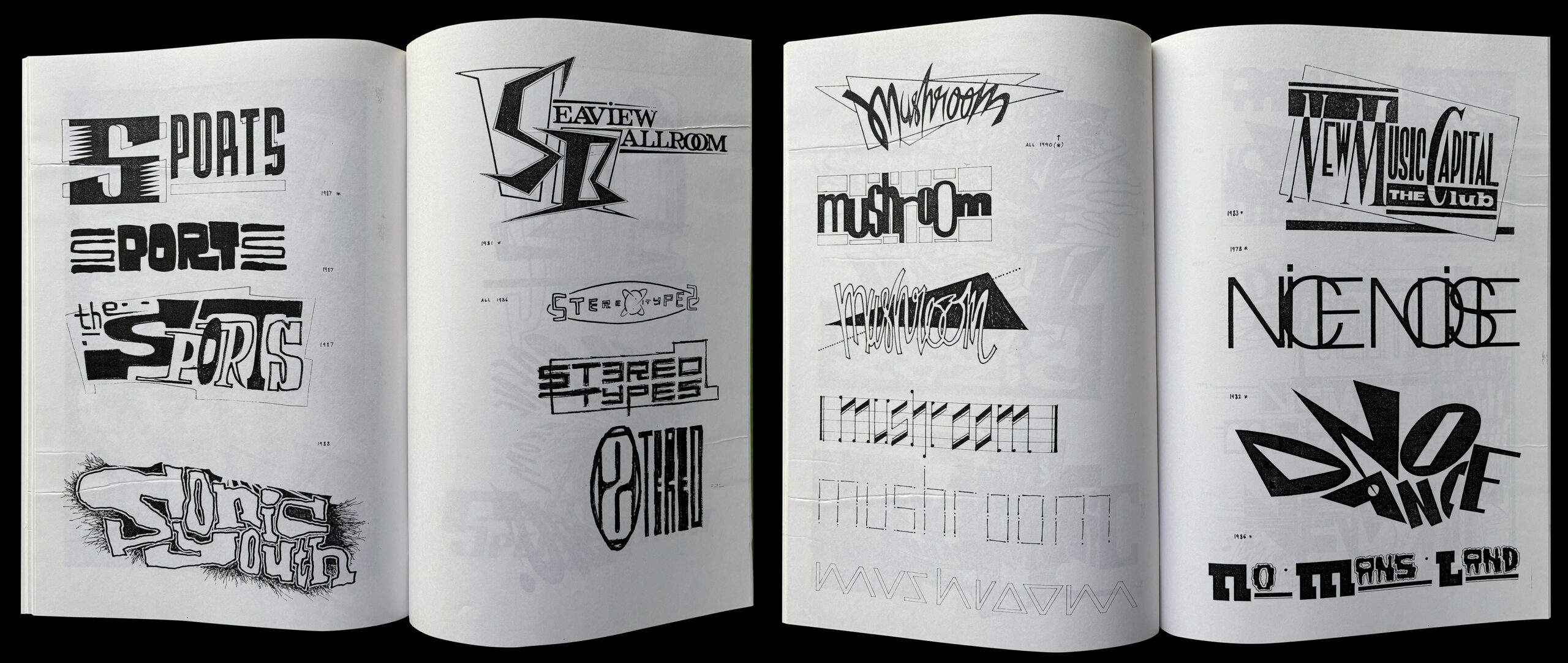

sb | We’re talking here about the series of publications: Stuffed Logos (1988) showed your lettering sketches for bands like The Sports, Huxton Creepers, The Dugites, Jo Jo Zep and the Falcons, as well as music hubs like the Seaview Ballroom, Missing Link Records and Augogo Records; Stuffed Alphabets (1988) critiqued the typography of monograms and logos; Stuffing (1990) centres on graphics (with texts on Post-punk, Edward Ruscha and Saul Bass). They all show that, underneath your own ‘doodling’ and ‘scribbling’ as you describe it, there was a very solid investigation with intellectual rigour. During that period there were not many people writing on graphic design with that intellectual engagement…

pb | I think probably there are two ways of looking at it. One is as you said, but the other is that I’m probably not any of those things. I’m not actually a graphic designer. I do stuff that ends up looking like it is graphically designed, but it’s almost like being a non-musician but then actually doing music. It was a kind of nerdiness because that’s what I spent my money on, records. And still to this day, I still buy records based on the record covers kind of thing. So, it’s still an important kind of, like, thing for me. I guess what I’m trying to just say is that for whatever reason, the whole thing about just being intellectual was always a pleasurable, fun, exciting and engaging thing to do. And when I was writing I just did it. Still to this day, I write without fear. I think people just need to loosen up and write whatever the fucking thought is in their head. It’s just an idea, it’s not going to bite you. I call it ‘material writing’. If you’re writing about a design object, write about everything you can see about that object. Don’t fucking tell me about society. Don’t fucking tell me about this, that, and the next thing all abstract. It’s got to be in the frame. And whatever idea you have has to be kind of inspired by something in the frame. Don’t bring your baggage to the image. Just fucking write what is there.

edited by Philip Brophy and Ian Robertson. Design by Ian Robertson. This issue offered a dense taxonomy of post-punk design and culture.

edited and designed

by Philip Brophy

sb | Stuffed is a humble production. It is photocopied and stapled together in a utilitarian, low-budget way. The perfect voice for that material.

pb | Yes, and all the artwork is hand-drawn. It was only probably around the mid 90s when I started running Freehand 10. I would draw it on paper, scan it and then kind of vector draw it. But no matter how much I tried I just couldn’t do it. I had this spontaneous drawing and no matter what I did on the screen, it just looked too ordered. It’s been interesting in the past ten years or so to see the revival of the hand-drawn hand letterform. The only problem is that it’s become the equivalent to what the whale poster was in the 1980s. It’s cheesy. It’s so rank, even though it is technically beautiful to look at. But where the hell is the idea? There is no idea.

sb | Stuffed Graphics is absolutely fascinating. And you were very kind to Peter Saville, I must say.

pb | At one point Peter Saville had a link to that essay from Stuffing. When Saville and (Malcolm) Garrett found out about that article, they were over the moon because no one was writing critique about that design work back then. It’s that thing where someone’s doing something but no one’s really appreciating what they’ve done. I think it’s because these probably more get bought by music people rather than design people, because a lot of the designs aren’t that great. You’re looking at them thinking it’s kind of an artifact.

sb | Stuffed Graphics was a fluent but lone voice. Why do you think there was nobody within graphic design writing about this?

pb | Because they’re just caught up with the mechanics of doing the job. The designer of Stuffing, Ian (Robertson), was caught up with surviving as a professional designer and yet he managed to write a thorough piece on Saul Bass. But then again, Ian came to graphic design not from an industrial kind of training perspective. He trained in fine art and specialised in screen printing. He did a whole series of posters in the mid 1970s with the collective Redback Graphics. He was really into design, but he was a fine artist. This is where, unfortunately, the whole thing is completely shifted since that period. There’s no longer a generation of graphic designers that are informed by that kind of art school knowledge. It’s all completely professionalised.

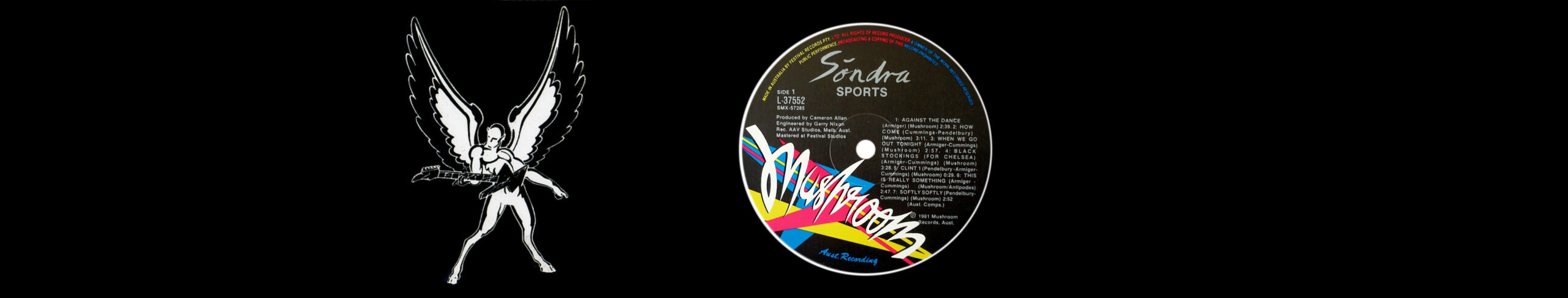

edited and designed by Philip Brophy, showing early iterations of logos for bands (The Sports), venues (Seaview Ballroom) and Mushroom Records.

sb | What made you decide to leave the field of graphic design?

pb | The most fundamental of these shift was when marketing took over for me. Because the minute you have someone else coming in who has no visual sensibility, no visual training or awareness of art history behind them and is essentially thinking, how can I get this product to market?

A very simple thing nudged me out of graphic design in 1980, or maybe even 1981, so very early. And that was when I did the Mushroom Records logo. In an hour and a half, I whipped up about ten different mushroom logos and took them down to (Michael) Gadinski. The manager of Jo Jo Zepp (and the Falcons) had got me to do their logo, because he wanted Jo Jo Zepp to look a bit new. I was doing this logo for these dudes, at the age of 18 or 19 or something, and so just did it, right? The manager says Gadinski is going to give you a call, as if it’s a big fucking deal. He calls and says I want you to give me a really cheap price on this logo, which in the end was $150 for what is now a famous logo, which even to me at that time, I thought, that’s a fucking lot of money, I just fucking doodle these things.

Then he said, you’ll give this one to me cheap, right, but I’m going to put, like, really fucking expensive kind of jobs your way, right? And so I said, yeah, okay. And to me, it’s just still a laugh. I can’t believe I’m sitting in this office because I hate the music, and pretending I’ve got a serious investment in considering anything that’s happening there in front of me. And so then I get a phone call from this guy, Lee Simon, one of those 70s rock style presenters. And they were like, ‘Hey Phil…’ they talk like they were in Los Angeles. ‘Hey, Phil, Mike put me onto you’. And he says, I really like your stuff for Mushroom. We’re starting up a fantastic new radio station. It’s going to be called Eon FM, and we want you to do the logo for us. And I said, okay. He says, ‘Why don’t you rock on down to the station and we’ll rap about it’. I go, okay, sure, thanks for the details. I hang up and I never fucking went. And that was it. There’s no way I’m going to fucking enter that domain.

Right: The Mushroom Records logo designed by Brophy.

sb | Yes, that EON FM logo was full of machismo…

pb | Yes, it was like a kind of a muscle-bound, Grecian, bogan, shithead, footballer, jock with fucking wings. Like Icarus with a guitar for a cock. That’s before they became Triple M then. The thing is that those f’orks in the road’ are presented to everyone at continual points, right? And I could have gone down that one. But even if I had gone down that one, there’s no way I would have fucking lasted there, you know what I mean? If you look at 70s Australian design – like Peter’s Ice Cream or Paul’s Billabong – just everything about it was so fucking ugly, personally and aesthetically. And of course, now I can look back on that stuff and see that it’s got some character even though it’s still ugly. History allows you to just re-evaluate everything. Maybe I was a young, self-centred narcissistic with an inflated sense of politics, but I decided that I wasn’t going to do that shit. I don’t judge anyone who ended up doing that kind of thing. It’s just not for me.

sb | Were you looking for further afield in your influences? Because I would have thought you’d be looking to figures like people like Barney Bubbles…

pb | No one even knew the name didn’t exist. That was the great thing about record covers, it was one of those areas where people were doing creative design. They weren’t doing art. That was the really important thing. These days, record covers are so boring because they’re ‘artistic.’ They’re not even designed.

sb | How much of this is due to a change in the design process?

pb | Yes, the software pre-decides all that stuff anyway. So they’re not even thinking, should I make it into Square on Instagram? They already fucking decided that for you. You did nothing. Whatever photo you’re taking with your phone, it’s vertical or horizontal, but it’s now square. No one’s deciding anything. You’re pulling down menus and you, oh, my god, I feel so creative. It’s like Sunday painting gone mad.

I think of the graphic designers operating from the late 70s into the mid 80s – by the time dance music and club culture comes along, record covers were still very important. Yet the actual design fee for the record covers was nowhere near as big as if they did a job for a high street boutique or franchise, so they then shifted into that. Like Me Company, they all diversified to survive as studios with overheads. My stuff was developed anarchically. I didn’t have fucking pressures on me. I’m not trying to discount my own work, but once you go into those bigger platforms, say if I theoretically worked on that Eon FM logo, maybe I could have done really interesting things. Or not. But we’ll never know.

This text is an edited extract from a longer interview with Philip Brophy in January 2022.