Australian Graphic Design B-Sides: AWWFAD

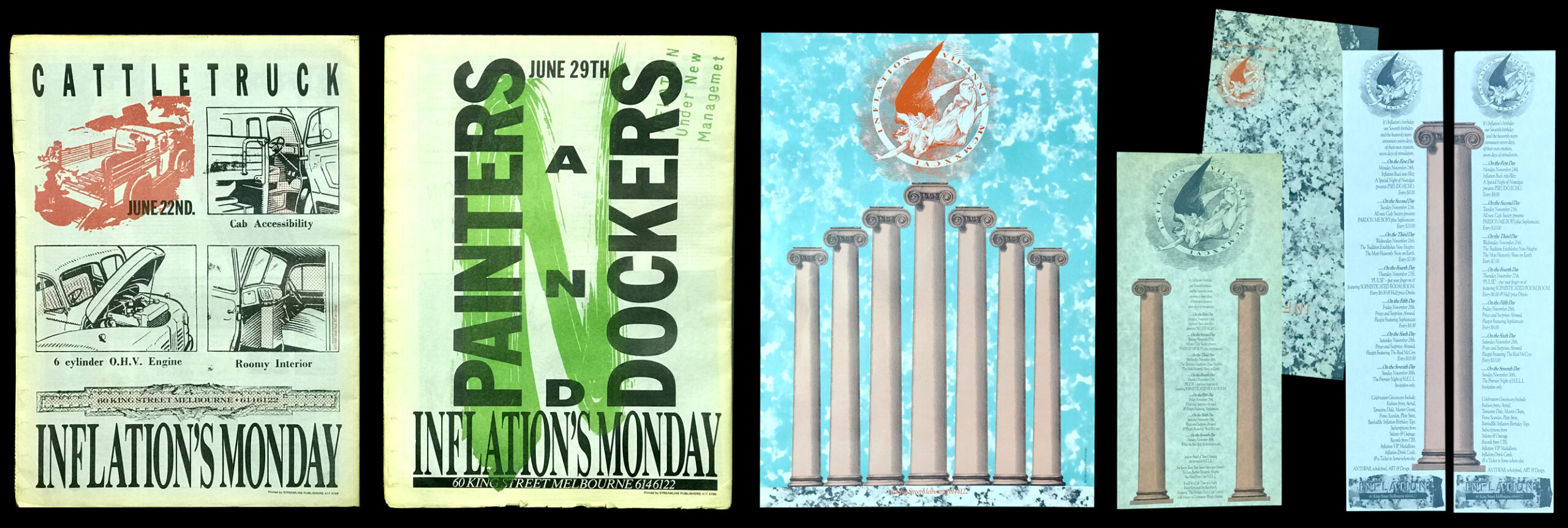

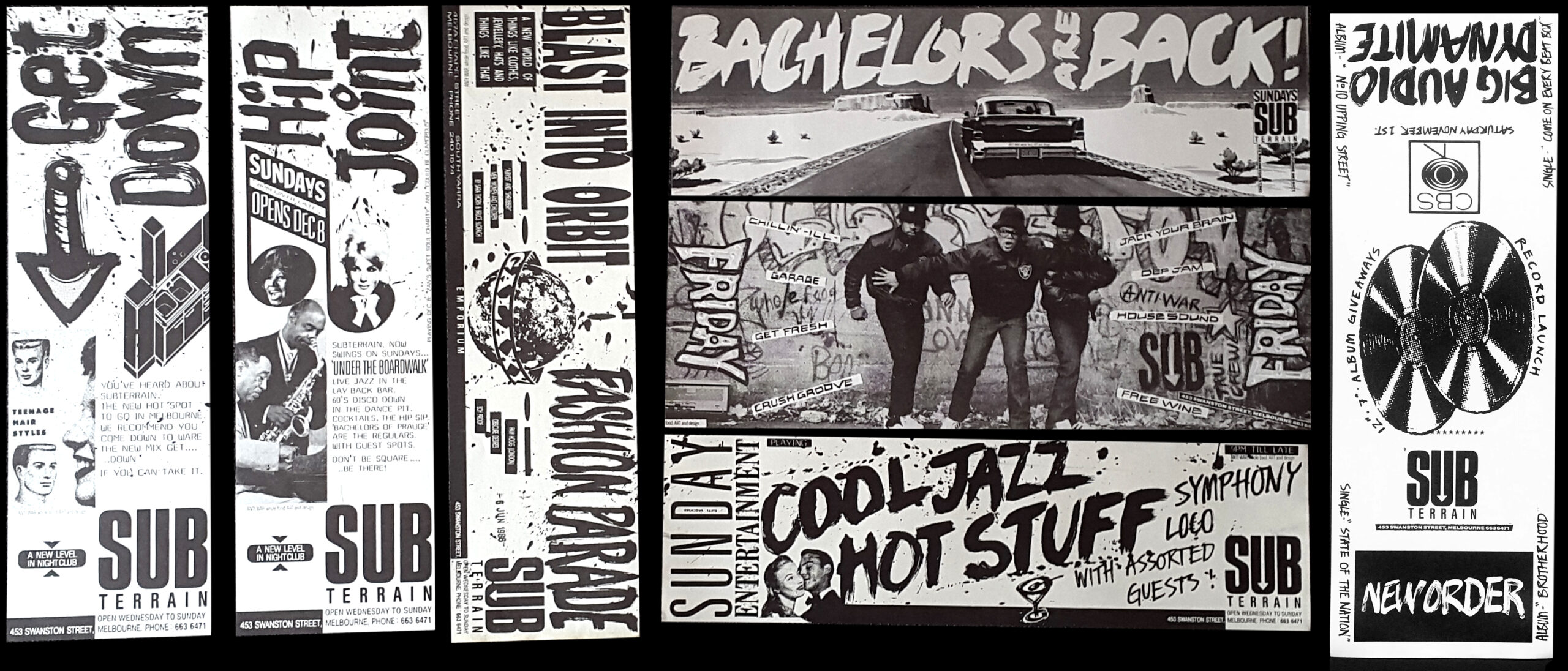

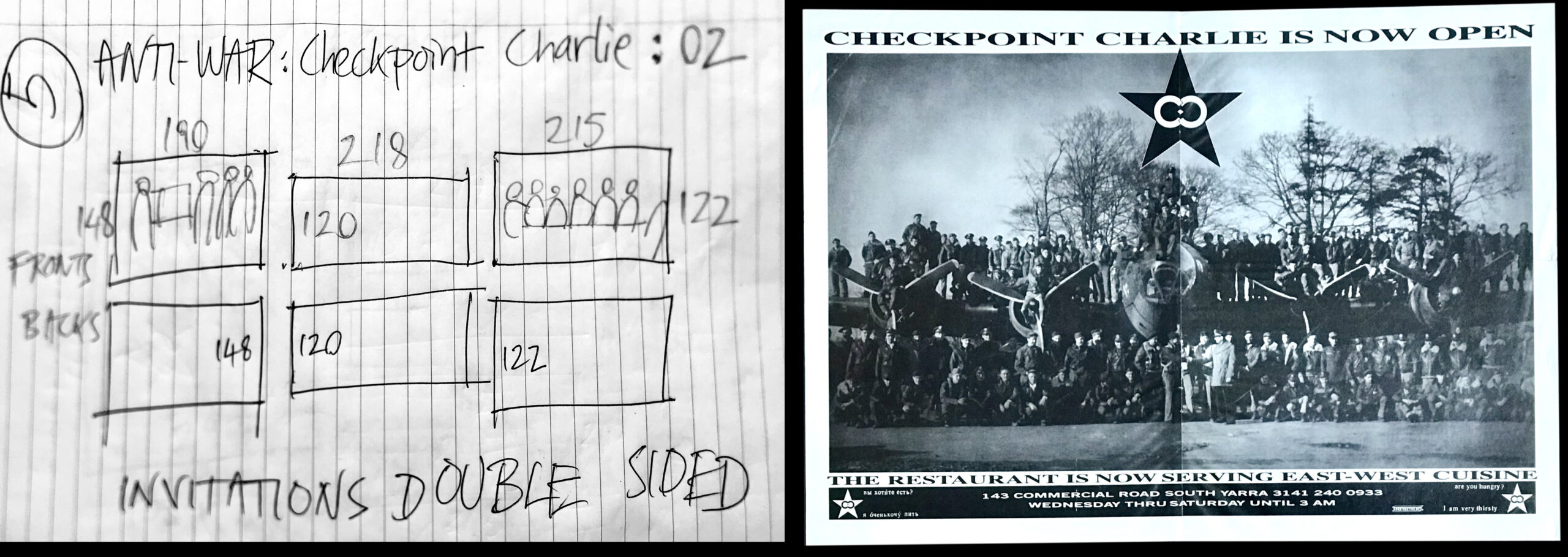

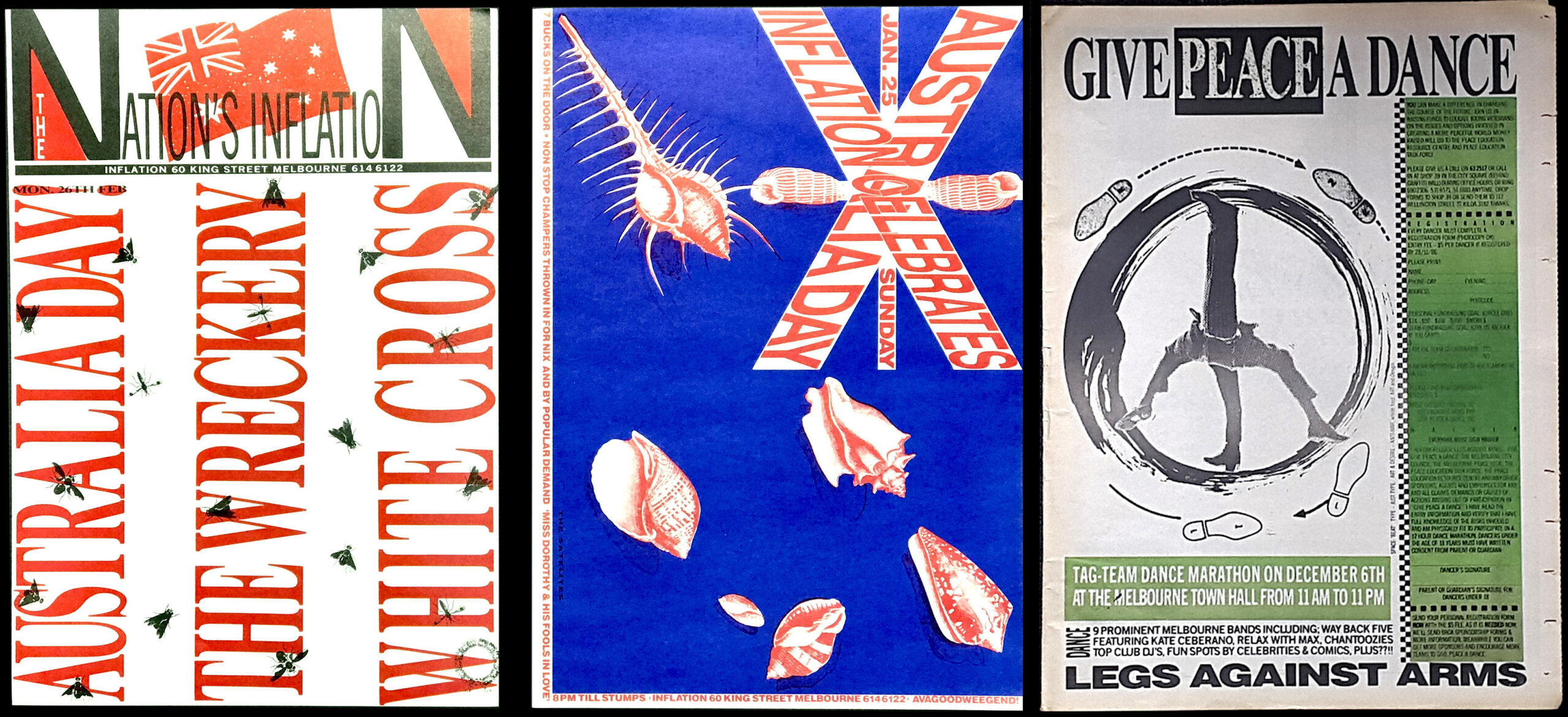

Inflation. Chasers. Checkpoint Charlie. The Old Greek Theatre. Subterrain. If you know of these 1980s Melbourne nightclubs then you’re probably also familiar with the design work of Anti-War Whole Food and Design (AWWFaD) without even knowing it.

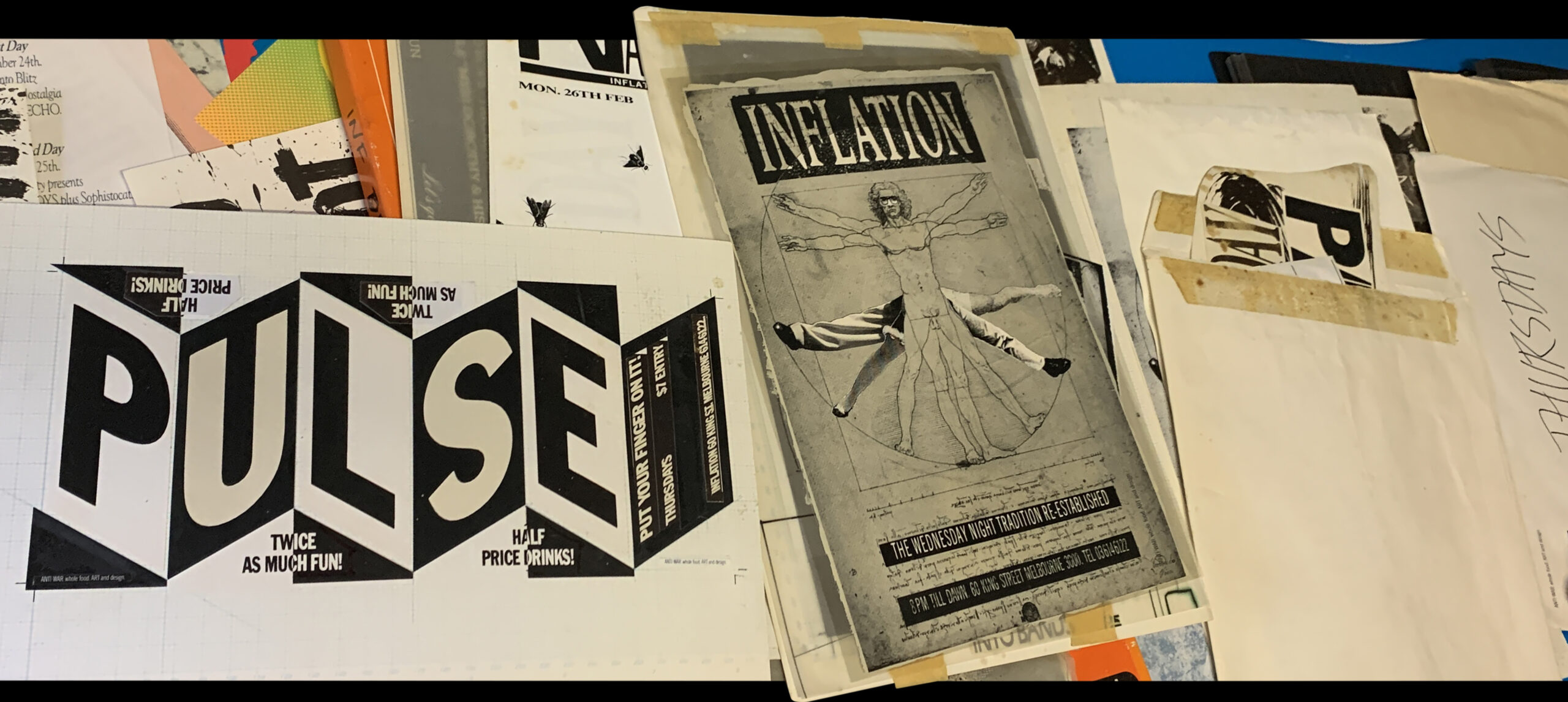

Their design personified a collaged postmodern style, echoing the fastly-edited fragmented videoclips popular at the time. The sheer ubiquity of AWWFaD-designed club flyers and press-ads during the mid to late 1980s renders a snapshot of an emerging nightclubbing scene in a pre-gentrified Melbourne. I discussed this with studio founder Jonathan Hannon as we looked through his archive in the lovely seaside town of Cowes.

sb | I first became aware of your studio because of its unusual name. I like the way it only really makes sense when spoken…

jh | Yes, I decided to call the studio anti-war whole food art design because of my own anti-war beliefs, coming from my Christian upbringing (my father was a minister of religion). But, yeah, the studio name is also a nice little wordplay on Andy Warhol and pop art.

sb | And when Beat magazine started up in 1986, there was finally direct media for clubbers?

jh | Yes. Some weeks I’d be doing four or five pages of ads in Beat Magazine, and I’d go there and I’d put them all in. Rob Furst (owner) would just let me put any little ad that I needed or wanted. It was fantastic. And same with my printers (Blueprint), I brought them so much work because of my work. So they printed anything I wanted to. It allowed me to make things, create things, and have them produced at no cost. That’s what’s wonderful about it when I look back on it. Because obviously when I do design work for myself, I did not have to go through that client process, the refining and then getting their approval. It was spontaneous. And some of my things I put in were like that ‘add inches’ campaign. Add inches to your height just by standing on your cigarette pad. It’s my own ‘dad joke’, humour, a quick response.

sb | So this material here spans what years?

jh | It starts in 85 and goes through to 88 or so. I was designing for, like, six clubs at one time, which is quite wacky because they were all competing against each other. You know what I mean? But they all said, no, we want you to do it. After that the work was more client-driven. In the early 90s we started out own fashion label, Bancusi. But we’re always struggling. I think you have to get over that hump and be a bigger business turning over 5 million or so. We were always tight, you know.

sb | That would have been a difficult period because of the tariffs and the whole manufacturing sector was in decline…

jh | Yeah. But at the time, we were just doing one day at a time and just spontaneously creating. It was a family thing. When my brother William, who had done sculpture at RMIT and modelling in Tokyo, came back and started the clothing aspect of Bancusi, whilst I always did the graphics. Will and I even got into Vogue because there was an article on ‘brothers in fashion’. When we were doing the Bancusi, we moved into 94 Flinders Street, a building where photographers and artists worked. We had a whole floor and built bedrooms on stilts.

sb | You’re talking about the era when people could rent a big factory space and just stick a caravan in the corner…

jh | Yeah, actually we bought a floatation tank. There were lots of rumours and gossip, you know, about us love and peace people would go in a float tank with three people and do what you do. People would be coming in to work at 9am, but because I’d be out late at night at clubs I’d be asleep in the float tank for a couple of hours. Crazy times.

sb | So is all your work print-based?

jh | Yes, it was all print and very fast turnaround. Very ephemeral. I would go to the printers at 4pm on a Friday and they’d turn it around. They knew I was coming. Then I’d be going around to all the clubs all night, which was great fun. At 3am I’d go to talk to the club owners and discuss the ideas, laugh and have a drink. Then I’d go off and design it overnight sometimes. I then got my own copy proof (bromide) camera, I just went into a studio that I used to work for and from, you know, 5 PM till 8 AM, and I work all night. Sometimes there was no real checking with the client because we had talked about it a couple of times and evolved the idea that way.

sb | What you’re describing there is a very informal relationship you’ve got with your clients. Was there ever a time when it went wrong?

jh | No. Not really. The biggest thing that went wrong one day was that we left a date off. So we had to go through and just do it with the date stamp. Damn. When I worked for various advertising agencies, I had a pet hate that they’d make a false deadline. I’d sometimes work really hard to get that deadline. And I remember one time I went into this guy’s office days or a week later, and the artwork was just still sitting on his desk…

sb | And what about your local contemporaries in design. Did you know Robert Pearce?

jh | Yes. He was at Swinburne with me, but 2 years ahead. But then, then I think what happened, we became major competition – a bit of a, shall we say, a ‘love hate’ relationship there. Probably less love more hate at times.

sb | And working during this time also bridged a lot of technological change.…

jh | Yes, even sending artwork off was tricky. In those days we started working on computers using those big discs. Those big clunky huge PLI cartridges. I went to, Ego, down in South Melbourne. You could hear them starting up, a very loud spinning. Sounded like a jet plane. And they cost almost $200 – for a few meg. Now you just email it off. It’s just phenomenal. I mean, people don’t get it. The process is so much easier.

sb | In my conversations with your design colleague Lin Tobias, she saw the evolution of the Macintosh as quite a turning point. She never really embraced the Mac, and that pointed towards her beginning to leave the industry and create her own artwork. So what made you leave graphic design?

It was my move down here (Phillip Island) that made me change. I had some great clients up in Melbourne who trusted me and knew I’d deliver. So I moved down here. I was studying to use the Mac in Melbourne, which I loved. It was a bit daunting for me, I must admit. Back then you could just press the wrong button and you’d lose everything…

sb | Looking across the entire collection of work, there’s a certain light-hearted-ness…

It’s not really taking itself terribly seriously, is it? No. It just catches people’s eyes. Whether you’re selling a spark plug or a drink or a night out, it doesn’t matter what you’re selling. Once you made them smile, they’re interested. We were also operating in a bit of a pre-copyright era. Yeah.

sb | Just on cusp of that. Yes.

In some ways this work could have only been from this period. You know? There are piles of elements there you just couldn’t do now. I agree.

sb | What about the typography for this work?

Well, there’s quite a lot of hand-drawn scripts and so forth. It wasn’t just artistic intention, it was also because it was just too hard to get stuff typeset at that particular time. It’d take a while because you had to spec it up and everything. I never concerned myself about the size I got them to set it to, because I knew that it could be enlarged or reduced to fit. I got some big sheets of graphics. Various bits and pieces. I’d sometimes splatter it with white using a toothbrush. And then splatter that with black.

sb | What about the actual the actual identities of the clubs? Were they pre-existing?

Yes. The one for Inflation was. So was Subterrain – but I made it better by putting just that little arrow. Pointing down below because that’s where the club was. Not everybody saw it, but some saw it and through it was clever. I remember that it was one of those nights, working all night and I just saw the subterranean logo and I just cut a little triangle of white paper and stuck it down, it was really simple. Almost like the FedEx logo…

This text is an edited extract from a longer interview with Jonathan Hannon in February 2023.

You may also enjoy another project centred on Melbourne’s club scene in the 1980s – Radical Utopias from the rmit Design Archives and rmit Gallery.