Mixed Business

Mixed Business: Integrating value systems with graphic design practice is a research study that focusses upon a selection of design practitioners whose studio structures have been specifically configured to bring their own value systems into their everyday design practice. This study was undertaken to address a common lament within the design community and explores viable alternative practice models, using direct discussions and case studies.

PARTICIPANTS IN THE STUDY

Claude Benzrihem

One of the principal designers in the Paris-based studio, Therese Troika, Claude has been practicing for over twenty years. The work of the Therese Troika studio is primarily culturally and community-based working, mainly for Museums, Institutes and arts organisations.

Tony Credland

Credland has been heavily involved in political activism for many years. He is perhaps best known in design circles as the designer behind Cactus network, producing Cactus and the Feeding Squirrels to the Nuts project. At the time of interview he was working in London as a designer for New Scientist Magazine.

Pascal Bejean

Pascal Bejean is one of the principal designers at the multi-faceted Paris-based studio, Labomatic as well as with the studio’s fine art practice arm, Ultralab. His Labomatic work is mainly based around the music and contemporary art worlds. He is the publisher and designer of Bulldozer magazine.

Peter Bilâk

Bilak’s Hague-based practice, Typoteque, includes a variety of roles such as graphic designer, writer, educator, font designer and contributor to the Dutch graphic design magazine DotDotDot.

Jonathan Barnbrook

Best known as the London type designer behind Virus foundry, Barnbrook has set up a practice that encompasses many spheres of design including music, film, contemporary art and advertising. He has been a major contributor to the Canadian-based culture jamming publication, Adbusters.

Studio Anybody

Made up of five designers, the Melbourne-based Studio Anybody’s practice is driven by research, collaboration and an active role in design education. Their work, centred around the fields of fashion, publishing and art, includes work for the Melbourne International Fashion Festival and Mooks.

Sîan Cook

A designer and educator, Cook lectures in graphic design at Kingston University, London. Along with her colleague Teal Triggs, she is noted for the formulation of Women’s Design Research Unit (WD+RU), an organisation for promoting the role of women in the design industry.

Paul Elliman

Once again based in London, Paul Elliman’s involvement in the world of graphic design is a complex one. As an academic, writer and designer, Elliman undertakes research projects on a regular basis. His design work has included work for Critical Mass, Wired magazine and the AIGA amongst others.

Inkahoots

The Brisbane-based graphic design studio is the product of an earlier series of co-operatives based around politics and social justice. Primarily working with mainly government and arts clientele, Inkahoots prides itself on being both independent and politically active.

Jan Van Toorn

An internationally renown design academic, Van Toorn centred his concerns around the role and responsibilities of the designer within wider media and culture. He was involved in activities including seminars, forums, workshops and is a former director of the Jan Van Eyke Academy. He passed away in 2020.

AGDA Victoria

As representatives of the Australian Graphic Design Association, John Frostell, Helen Watts, Max Robinson & Jody Fenn span many generations and professional experiences. Their contribution offered a localised industrial perspective.

Works by (1) Paul Elliman

(2) Studio Anybody (3) Jan Van Toorn (4) Paul Elliman

…you become a ‘temporary expert’ on projects, and try to find out as much as you can…

the importance of direct involvement with project content

A fundamental factor in the alignment of values to professional practice is direct involvement, particularly contributing the authoring of content. With this direct involvement comes a more thorough understanding of content, especially when the designer is introduced early in the process. The shifting of the designer’s role from that of latter-stage visualiser of information to a more fundamentally engaged role has been very much at the centre of recent debates and is pertinent to this study.

In the case of English graphic designer, Tony Credland, who brings to his work a direct involvement in politics and social justice, the alignment is paramount, “Politics and design overlap. I don’t just work as a political graphic designer, I work as an activist, doing video covers, brochures, leaflets etc as well as training people, sharing skills. Then there’s the teaching. And that is usually done within a political framework, suggesting different ways of working and discussing social responsibility’.”

As well as minimising any potential ethical conflicts, direct involvement throughout a project allows for greater capacity for the designer to more readily identify with the end-user of the information. It makes the process of the project more enjoyable and satisfying. When English designer and educator Paul Elliman was asked to design for the cycling activist group Critical Mass he immediately saw the possibilities of a pre-existing involvement with the group. “I cycle with Critical Mass– it’s an easy ‘client’, actually it’s anonymous, there is no client. I mean I’m as much a part of Critical Mass as anyone is, you know, it’s not even an organisation – it’s referred to as an organised coincidence. Anyway, the work I made is a straight-forward ‘call to arms’ that stems directly from a position of believing in Critical Mass and believing that it has an impact on the place where I live.” Elliman continues “… I think that my contribution works on a number of levels. You can appreciate it as graphic design, for example. But also I wanted to convey a more sensitive, less aggressive dimension to Critical Mass, perhaps in contrast to how the group is usually portrayed. The recycling thing for example – I mean obviously a prime concern of the city cyclist is a healthier, safer, more sustainable living environment. Then there’s the A-Z map by Phyllis Pearsall, which makes another set of connections, brings in other values. It’s about the city, discreet parts of the city, the ways in which our use of the city is organised, prescribed. In the end I hope the graphic design itself does a number of things as well as being chiefly a promo for a pressure group. And I felt like I was collaborating with Phyllis Pearsall, or that we, if I can say that, were working somewhat collaboratively with our city. My wife, Ingrid, once told me that I seemed to be generating a black hole within the cosmic slop of graphic design. She was referring to things like the Critical Mass project, or my Bits typeface for example. I think she meant that while I could probably operate as a graphic designer in a reasonably sophisticated way – you know, with skills that an agency might employ, for example – here I am deploying this practice in another space. A kind of inversion of that particular representational space. So, for example, in some ways I’m taking design values that I may not even believe in, and using them for something that I do believe in because I find the contradiction in some ways necessary or useful. I think that it goes without saying that I do these things because of certain values and beliefs that I have with regards to living in the city. Mediating, or simply coming to terms with this relationship through what we know, love and hate, as graphic design.”

…(involvement) takes you away from discussing ‘oh, this typeface, that typeface’…

Given the opportunity for the designer to have direct contact, knowledge of and empathy with, the end user is a clear advantage as it provides insights that assist the generation of both content and form. London-based graphic designer and educator Sîan Cook says of her personal and professional involvement in safe sex hiv-aids education programmes, “The organisation I am working for at the moment, that I do pro-Bono work for at the moment, is an organisation called ‘Gay Men fighting aids’. It’s a volunteer organisation, they have a very small staff. They do a lot of advertising campaigns and it all comes from volunteer groups. I will come in as part of a group to work on a campaign but I am an equal member of that group. I’m the designer so at the end of the day, I will have to realise the work but the ideas might not be mine. It might be another member’s idea and we’ll then sit down and discuss how it will be realised. It is a far more democratic way of working. These people don’t have to have a trade qualification in design to have a visual literacy. I find that really stimulating because it takes you away from discussing ‘oh, this typeface, that typeface’. Sometimes I would suggest something, saying ‘well, I think this imagery would work’ and they would say ‘what!? no gay man would look at that!’. It’s really heartening, you’ve got the audience there. To me that’s a lot more exciting way of working, rather than in a remote, detached sort of way”.

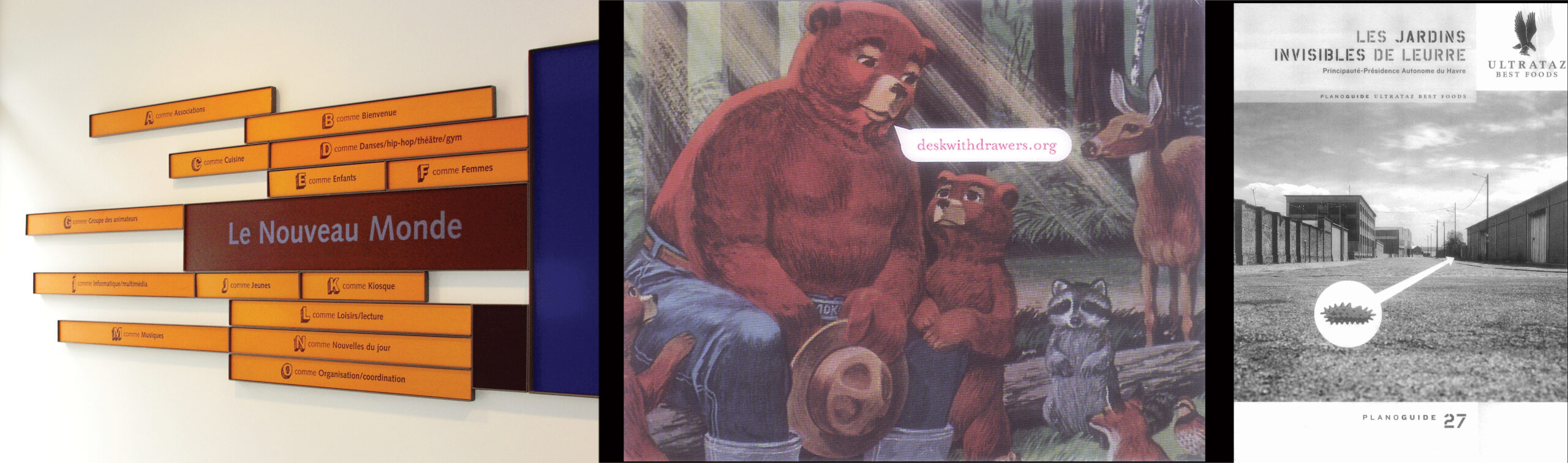

Although involvement throughout a project may sound straightforward, the designer must firstly ensure that their values fit the project itself – and that is where pre-existing involvement or disposition plays a defining role. When the French design group, Therese Troika was approached to design the signage system for a new community centre in an underprivileged Paris suburb, their immediate reaction was to investigate the communities who were to use this facility and make sure that the naming of the centre and everything it represented was culturally appropriate.

The social-cultural centre, situated in Villeneuve-la -Garenne, serves a community of primarily North African immigrants. It is a welcoming place for people of all ages living in the local area. A variety of associations operate from the centre as do a myriad of social activities – cooking lessons for young mothers, French language classes, information forums to educate people about their civic rights and the possibilities of employment and family-based activities. The Centre itself is part of a larger and more ambitious cultural project – the rehabilitation of the city district of ‘La Caravelle’ in Villeneuve la garenne. The area features buildings originally designed in the sixties by the functionalist architect M. Dubuisson. Comprising of some four thousand apartments, it was one of the biggest housing blocks in Europe and was later rehabilitated by the French architect, Roland Castro.

The first issue for Therese Troika was the naming of the Centre. The local council had named the centre ‘The New World’. This unfortunate title conjured up inappropriate and even potentially provocative notions of alienation, foreignness and above all, a western colonial arrogance. As Claude Benzrihem, member of Therese Troika, put it “Along with the architect Isabelle Crosnier, we worked from the very beginning of the housing architecture – the choice of colours, choice of furniture and materials. Our teamwork was heavily based upon regular encounters with the users of this place’. It is through this level of engagement that produced an overall idea as to what was needed. “Our project was based upon the idea of modularity, flexibility and evolution. The signage itself is like a toolbox, a free composition of modules –images, texts, coloured spaces for expression, and possibility to leave temporary messages. The actual signage structures themselves are metal frames, in a variety of sizes from A6 to A3 and larger, freely composed around each other. The organisation of the messages is composed like a game : A is for Association, B is for Book, C is for Chats, D is for Dance, etc. The visual memory has as much meaning as the memory of the text. Many people who are coming here don’t speak French very well and so can find language-based orientation systems difficult.”

Direct involvement is strongest in community and culturally based projects – developing the relationship from working for the community to working with the community. As Tony Credland recalls his experience working in the political activist communities “Whilst at the Jan Van Eyke Academy, I met with Gerald Paris-Clavel and worked with Ne Pas Plier (Do not bend) in Paris for a month. The way they did work was very inspiring. They approached the work by listening to other communities; they didn’t try to impose their design on people. Design was just a way of communication rather than a process unto itself. They would employ design for political ends and use it in very innovative ways, but very specific to Paris”.

Involvement can also help to focus the designer’s input away from the aesthetic to the functional – opening up possibilities of using process and content as primary ingedients. When English graphic designer and educator Sîan Cook described the formation of work of the Womens Design Research Unit (WD+RU) with colleague Teal Triggs she noted “Not much of what we do at WD+RU is actually graphics output per se, a lot of our work involves giving talks, writing occasional articles for the design press, hosting discussions, talking to people and providing book lists, references and the like. It’s not a concrete outcome. We started in 1994 to promote the role of women in design. That situation has got a lot better since that time. We had the unfortunate problem of everything that we did being judged on its design values and that wasn’t the point. It was as though we had to be shit-hot designers to prove that women are good designers. What we really wanted to do was to change how people valued design – so it wasn’t about how good things looked but more about how they worked. So we deliberately went against that, not trying to make things look flash. There’s no reason why women can’t do that as well as men, but are we interested? Do we want to compete on that level? No. We’re informed by many core feminist principles – the idea of working with a community or not being overly concerned about aesthetics but more about whether they work”.

Conventional modes of graphic design practice have emerged from a prevailing modernist mindset that positions the role of the designer as rational and detached. Reflecting on an earlier point in her career as a graphic designer, the design educator Katherine McCoy notes “During that year (1968), the designers I worked with, save one notable exception, were remarkably disinterested in the social upheavals taking place around us. Vietnam was escalating with body counts touted on every evening newscast; the New Left rioted before the Democratic National Convention in Chicago; Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy were assassinated; and Detroit was still smoking from its riots just down the street from our office. Yet hardly a word was spoken on these subjects. We were encouraged to wear white lab coats, perhaps so the messy external environment would not contaminate our surgically clean detachment. These white lab coats make an excellent metaphor for the apolitical designer, cherishing the myth of universal value-free design. They suggest that design is a clinical process akin to chemistry, scientifically pure and neutral. Yet Lawrence and Oppenheimer and a thousand more examples teach us that even chemists and physicists must have a contextual view of their work in the social/political world around them”. As English type designer Jonathan Barnbrook adds to this sentiment in his own words: “Lots of designers would say that we are transparent messengers of the client’s message. I’ve never been into that myself. I’m certainly not a subscriber to the ‘Crystal Goblet Theory’”.

the natural state of values

Many practitioners including, Paul Elliman, saw the process of engaging with content as completely natural — “I think I would always find it difficult being a graphic designer in situations where I wasn’t somehow integrally involved. My first practical experience was at City Limits, a London listings magazine with a clear political agenda, and one that I felt I agreed with. I think its important to know that I became interested in graphic design after joining this magazine, and not through any prior, specifically graphic design-based interests. And then my second job – and here I was much more involved as a designer – was at Wire magazine. But here again, having had a strong interest in jazz-related music through my teens, I was already a reader of Wire, and to become the magazine’s designer was perfect for me at that time. But when I finished at Wire, I found it very difficult to see myself as a ‘designer for hire.’ Whereas other magazine designers tend to move from one publication to another. That’s how they identify themselves. They might not have such a partisan attachment to the content of any particular magazine. They might just want to design magazines. OK, that’s an over-simplification, but what I’m saying is that I felt able to engage with Wire magazine on a number of levels, a commitment that wouldn’t be easily repeated elsewhere. For that reason – although it’s not the only reason- the idea of continuing to be a magazine designer, or even a designer, didn’t necessarily appeal to me, and still doesn’t particularly.”

Although every project is different in its nature, scope, audience and message, each offers its own opportunities for learning about a particular field of knowledge. The designer’s capacity to learn is constantly expanded, broadening beyond design. Hague-based designer Peter Bilâk has been a long time exponent of perpetually learning from projects. This was reflected in his comments on the difference between self-initiated and client-led projects; “Perhaps it would be too simplistic to say that there are no differences because there are differences. Sometimes I wouldn’t think about working on a project until you get asked. So client-initiated projects are a very integral part. It opens you up to new things whereas self-initiated projects are things that you want to do, want to explore. I just got a commission in France, working in the city of Norsee and I had to come and do the research because I didn’t know anything about it. Being on-board this project you have to find out. I like design in this way, because you become a ‘temporary expert’ on projects, You try to find out as much as you can or experience”.

Bilâk continues “In every project there has to be something which makes you want to do it. That something can be a potential, you know, working with people you want to work with, it could be things that I always wanted to discover but not having time to do it myself. I don’t know whether I could describe that my value is… this. Sometimes I deliberately take on a difficult project because it forces me to go further. We have been working with Stuart Bailey on a book on Dutch design, and there have been many books written on Dutch design and we know that people say ‘yeah, yeah, another book on Dutch design’ but we took it on because we think that it can be presented in a different way. We have some ideas as to how to do it. We know it is very difficult. But we still want to try. This afternoon I am going to Germany because I am working for the Holocaust Museum in Stuttgart. When I was first approached I think that in principle it sounds like a worthy thing, I like to share my energies for a good thing. Sometimes I accept a project because it is technologically innovating. I am working on a project which is only the programming but I thought I would benefit from working with people who know a lot more about it than I do. So there is always different things. I like to see design as the natural result of the research. It’s so obviously connected, so you can say of course it looks like that because of the research that I have made”.

…To remove this aura of inaccessibility, to explain these things, to say that this is the result of a whole machinery, how a country functions, this was the intention…

When Peter Bilâk was posed with the challenge of putting on an exhibition of Dutch graphic design, his values of criticality were manifest in a solution that stripped back the aesthetic exterior of the graphic design artefact, exposing an underlying system – the commission itself. “This is a promotional card for an exhibition of Dutch Design I curated at the Graphic Design Biennale in Brno two years ago. The thing was how to present graphic design to the public and it was a very good exercise for me because I could get involved and organise it from the start. Presenting graphic design in a gallery space is forced and rarely works but we had to work with it. Taking the design from another country and presenting it somewhere else is also very difficult because often people just romanticise and present it as a set of beautiful images, you don’t understand why they were made or how. To remove this aura of inaccessibility, to explain these things, to say that this is the result of a whole machinery, how a country functions, this was the intention. For this exhibition project, I would make a selection of people I was interested in and then try to work out the client they are working for – because they play a crucial role. I talked to these clients, collected all the briefs, if any, and presented these with the work, in some cases stating that there was no formal brief. And then you see that the work is the result of something. To draw this it would be a triangle – the designer, the commissioner and the public. For me it is about showing what you doing, taking away those ideas of exclusivity.”

Through involvement and research throughout projects, many designers create a most fertile environment for developing one’s own vocabulary. Melbourne-based Studio Anybody insist on having their investigations and research couched within their valued collaborative structure. From their experience this results in their work being recognised through process rather than ‘style’. “…By research or by bringing into it your values, can create an alternative mode of practice. I think it is quite evident in the work itself that our values lie in that, that there is a feel , a personal feel to it. Sometimes people will say ‘oh, that’s seems very studio anybody’, they tend not to say ‘oh, that looks like studio anybody’ because maybe it’s not house style. …I think it would be a particular type of client that would be interested in that. By its very nature, self-initiated work is very personal and I think that graphic design, by its very nature, is problem-solving for someone else. Though I do think that a lot of our work uses both. We have some clients that may want it to be more a case of graphic design – of graphic elements, less the conceptual side. We’ve worked a lot with arts organisations and generally it works but I know that one or two case they have said ‘We don’t want you to make the artwork, we want you to represent the artwork’. And they don’t see how you can do that with some sort of conceptual image. It has to be base graphic design. Our success, particularly in the earlier years, was that our work was open-ended. And which has now been brought into the client work. I don’t think you should make a distinction”.

These ‘expanded languages’ can emerge out of long-term investigations into topics not readily related to graphic design. Paul Elliman refers to this in relation to a very specific project, the design of the American Institute of Graphic Arts (aiga) conference. This project drew together and applied his previous research into test patterns. “I think any relationship between what I believe in and what my work is, has both intensified and become more subtle. I hope so anyway. Through a combination of having a bit more experience and becoming curious about finding ways to engage with projects that I may initially think I have less in common with. The work I did for the aiga is one example. I was asked to design material for one of their conferences and found that my interest in test patterns could be taken further through this project. …Test patterns are beautiful, quite abstract, can seem very aesthetic, and even, as a kind of ‘pseudo-neutral’ form, appear to have little to do with one’s values or beliefs in any socially concerned way. But it shouldn’t take much to find the significance of addressing the material nature of our technology through a set of highly engineered diagnostic tools. It should also go without saying that any exploration of the codes and languages of your work will have political and social implications. Not to over-read the project, of course”.

finding your own values

In an industry where graphic designers tenuously align their own ‘success’ by proxy – through either the financial worth or creative kudos of their clients. A longer-term strategy may be to create differentiation through articulating one’s own values. Clear positions on integrity, philosophy or politics has the defining effect of attracting appropriate clients whilst repelling inappropriate ones. This closer relationship deepens an empathetic working process and approach.

In large cosmopiltan hubs like Paris, practices such as Theres Trioka are more readily sustained and given opportunities to clearly define their values and position – “When we write the method of working, we always explain how we want to work. And some people when they see this, they say farewell. But at least everybody knows where they stand.

“We don’t like to be like the butcher delivering meat on a bicycle. We prefer to work with them not for them. When we can’t do that, then we are not useful.”

At the very beginning we started doing culturally based projects. In that time, when we started in the 1980s, it was easier to do that. There were a lot of commissions. We worked on a large museum commission and then we started getting more jobs like that. Until we got to a stage where we could say no to the jobs we didn’t want to do. Our work was mainly navigational and signage-based. If we fit with the project, then we do the project. If it fits then we get involved, part of the team, so we are inside and we think with them. We don’t like to be like the butcher delivering meat on a bicycle. We prefer to work with them not for them. When we can’t do that, then we are not useful.”

For Studio Anybody, involvement by clients is one way of ensuring a ‘fit’ in their collaborative approach “If you say that you’re going to collaborate with clients, it’s a two-way thing. It’s not necessarily a process that everybody wants to get involved in. A lot of people just want the job done, they don’t want to be confronted by questions, generate content – they just want results’. This ultimately suggests that the defining their client base is a positive thing ‘In a good way the clients that don’t want to participate in our process don’t.” Just as this process can reinforce sympathetic clients, it can also limit the range of clients willing to be collaborators. Jason Evans acknowledges this impact, “The other repercussion, which can be fairly negative, is that some people say of us ‘They’re too conceptual, they’re too precious. They wouldn’t be right for us, they do art projects. In a commercial environment our process can scare many people away’. Once this negotiation with the client is resolved, Studio Anybody projects can then progress with a strengthened consensus.”

Brisbane-based studio Inkahoots are unapologetic about their politics and its capacity to either encourage or repel potential clients. One of the more light-hearted instances of this is recounted by Inkahoots co-founder Robyn McDonald “Just recently we did the exhibition stand for the Crime and Misconduct Commission, they’re a government body who have taken over from the CJC, the Criminal Justice Commission. When you apply to be a preferred supplier, they check up on police records. Jason and I both have been attending marches for years and therefore both have special branch files. We thought that this would be an interesting result but they didn’t knock us back. I think it is perhaps because people are more broadminded in those positions these days – maybe if we were still in the Bjelke Petersen era we would have found it harder.”

Rather than be put off by such experiences, Inkahoots actively seek opportunities through which their political views can be aired “We’ve just made steps towards forming a strategic alliance with the Queensland Council of Social Services (QCOSS) who are the peak body working for a better deal for underprivileged people in our society, working towards social justice. They also have a program where they were advocating people in business to work in partnership with charitable organisations and foundations. So we would do our design work for half the normal rate but we do all of their work – they desperately need re-branding. That way the work will be promoted to their client base, all the community organisations working in the social sector in Queensland. So that helps to put our name out. QCOSS put out a newsletter about four times a year and they said ‘oh, you could do a column on design tips’. We said ‘well, actually, we would rather talk about Inkahoot’s political view on current events’. A forum where we can put forward our political viewpoint (incomplete sentence). This strategy is one way of staying viable so we don’t have to go out of our community, cultural and government sector.”

In Tony Credland’s experience, following political beliefs into practice empowers the individual to avoid potential clients who may not respect those beliefs “There’s no client out there who will come to you wanting a political edge unless they are going to use it as a selling drive or marketing ploy. Some magazines have come to me saying ‘There’s this free magazine and we want a bit of politics in there, can you do something for it’. But it’s going to be covered in adverts and that’s just there to sell the magazine. Basically it’s just a style magazine and they just want a bit of politics for their content and I don’t want to be part of that process. I don’t have to rely on that form for my politics, I can go and make my own magazine. I don’t need to use somebody else’s magazine to get my politics out. There’s more grassroots ways of getting that content out”.

Value in practice does not only effect who you work for, but also how you work. Paul Elliman’s experience as being a designer who has a clearly more considered but much smaller output has orientated the course of this working life. “It’s somewhat Darwinian in the way that it has forced other strengths to develop. But of course it will have in some ways limited my options. To be honest I’m ok with that because I’m someone who prefers a smaller, more selective output. Without being too precious about it. But rather than churning things out, perhaps spending more time thinking things through, developing interests and themes. I don’t necessarily think that the other ways of working are wrong or bad or anything. I can still admire people in more orthodox studio practices who work faster and produce more. That’s graphic design really and I think that can be fine. For myself I need to take a slower approach and one result of that is a smaller output of work. But then that has led me to find other ways to get by. And these have supported and maybe even extended my thinking. For example, through writing or teaching, which I see as equal parts of what I do – designing, teaching, writing. Although I still feel that the impact of producing less work has, in a formal sense, probably slowed my development. Even though I somehow had an instinct for design from an early age — I was still quite young, about 26, by the time I left Wire and even if I might have looked like a quick developer it was a painful learning curve at the time — but that was a one-off thing and then I chose to drop out of design for a few years before working my way back in from another direction. And I became even more selective about the work that I was taking on. As a result then, I think the development of how I work, formally and conceptually, was slowed by not having a continual output, but then it became something else. So not really a problem’.

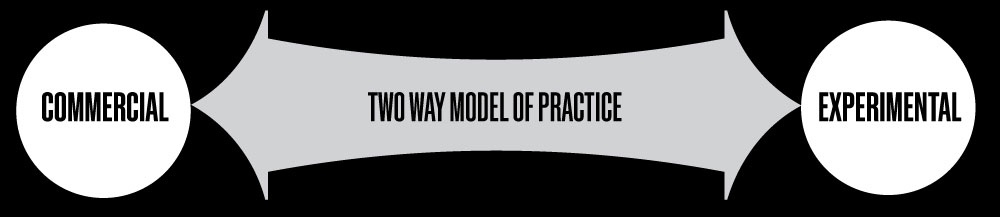

One of the most challenging and divisive terms used in a study such as this were the terms ‘commercial’ and ‘non-commercial’. Dispensing with these terms ultimately proved to be a wise one as the practitioners interviewed were not only adamant that a distinction should not be drawn but that the terms themselves inhibited the integration of values into practice. This point became central to the research, significantly influencing the outcomes of my own practice. Scoping out from the narrow confines of one’s own field allows for a greater cross-pollination of skills, ideas and opportunities.

“It’s a funny idea, the idea of doing your commercial work during the day and going off and then in the evening doing your nice little designs. You just do your work”.

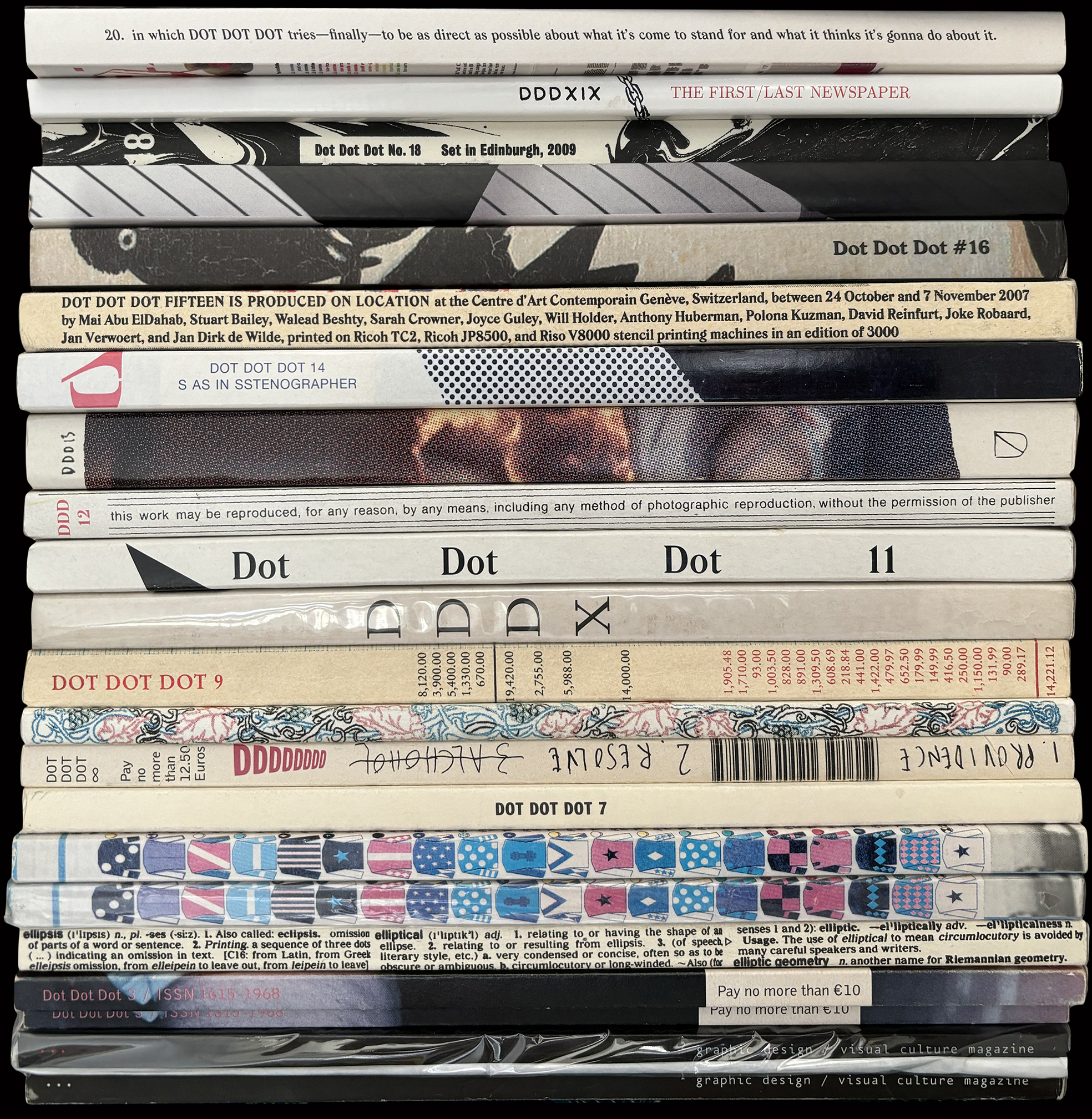

A strong advocate for a more unified approach is the Slovakian-born, Hague-based designer Peter Bilâk. Reflecting upon his own practice, he noted “It’s a funny idea, the idea of doing your commercial work during the day and going off and then in the evening doing your nice little designs. You just do your work. DotDotDot (magazine) is just as much part of my work as anything else I do. It’s not like I save it for the evenings. In a way I don’t have a project that would be like that. All my living is made by things like this – making books, writing for books, the fonts, organising exhibitions – and all of them, they are commercial because I get paid for it. I mean, DotDotDot is also for sale so I don’t know when things stop being commercial, or when they start being commercial. I do it because I like to do it and if I can make a living out of it then that’s even better.”

Within a Dutch cultural context, this integrated method of practice is not considered unusual at all. “…But the other thing is that it’s fairly common, it’s not unusual doing this. Our studio is a good example of similar interests getting together. It has obvious advantages to it, why we work like this. Most of my friends are doing the same – combining work with cultural institutions. It’s their work, they like doing it. They participate in the exhibition of the projects. Some of us are also involved in teaching, so having this life with bits of teaching, bits of this, bits of that and that’s your work.”

Like Peter Bilâk, English designer Jonathan Barnbrook views the division of the two forms of projects as problematic “I see the separation of the two as a flawed way of working. In that it’s a separation of the self from the work. It’s important that you contain what you do in the commercial content as well – people come to you for the work that you do so you have to show that. And if you’re never doing the kind of work that you really want to do then they’ll never know that. So just be great in the first place.’. Barnbrook certainly lives his own theory in his work, making a smooth transition from working on a corporate identity project to designing one of his own typefaces in the same day “Both commercial and experimental work are self-initiated. They both come from the self, they’re not separate. The only difference is that you have a time-frame and a brief that you don’t necessarily have on your own projects. It is appropriate for them to co-exist because they are one.”

Some designers construct methods of maintaining their values across the differing natures of a variety of projects. One such strategy is to name the studio’s different pursuits under different titles when in fact they emanate from the same designer. Pascal Bejean describes the process by which Labomatic (the design arm) and Ultralab (the fine art arm) relate to each other – “I don’t think we can think differently in one place to another one, or in Winter or in Summer. Especially since our tools are the same. We work with graphics, graphic design is our artwork. And we try to input our approach in the design of the work. So it is very mixed.”

Claude Benzrihem of Therese Troika puts it more poetically – “The projects are considered to be the same. Because the commercial work we do is the work we choose to do. It’s all one whole thing. Sometimes we are not well paid but we choose what present we want to give and to whom we want to give it. (Yet) we pay the same amount of attention to all of them (the projects) …. But that’s a choice. We try to make it the most sincere it can be”.

The conventional view of self-initiated work within a studio is that of as free space that allows for the exploration of ideas to be tested and then steadily introduced, either entirely or diluted, into the commercial arena. This flow from the ‘experimental’ to the ‘commercial’, need not be one-way. Values could be brought into both the ‘experimental’ and ‘commercial’ realms, allowing the flow of ideas to be two-way. Jonathan Barnbrook is a strong believer in this approach “Because of the nature of the kind of commercial work we get, it can often lead on to private work. So it ends up being the other way. We have generated two or three typefaces. Quite extreme typefaces, that were triggered by a commercial project. So it’s not that the self-initiated projects are the breeding ground for the commercial work, it can be the other way around. It was the Public Offerings book, out of which came Expletive Script. But I suppose it depends on the nature of the job – an art catalogue rather than a company report for instance”

the breadth of value systems

This study has highlighted the sheer breadth of values held by designers. Some values were socio-politically orientated (Inkahoots or Tony Credland), some are process-based (Studio Anybody) whilst others are aesthetic (Pascal Bejean) or humanist (Therese Troika or Jonathan Barnbrook). Yet this range of values were all bound through criticality and self-reflection. More varied however were their ways of implementing these values into practice – some such as Jonathan Barnbrook found it easier to make a ‘macro’ description – “The fundamental thing about design is trying to make the world a better place with it – whatever form that takes. It should be the basis of all work. Those things ARE quite simple in the end. Design should improve society. The desire to be a good human being cannot be separated from doing graphic design’.

Therese Troika has no difficulty in articulating the value system by which they practice – “Sincerity is the one thing we always want to develop. That would be our value in one word’. They emphasised its importance by its absence in much contemporary French graphic design ‘If you have been to Palais de Tokyo here in Paris, M/M did the signage. It’s completely trash. I don’t like it very much because it is for an institution. It was as if the institution had taken ecstasy. It is not the role of the institution. It’s a sign of the times. The bookshop is like a cage. The books are inside; the prices are written in a scribble. It’s a parody of what happened in the artists’ workshops in the 1970’s or a building site only with security. Everything is apparent. It’s ostentatious and only for a very rich audience. It’s the look of no look. It is not sincere”.

Personalising beliefs is a way of contributing not only to the practice but a more universal code of conduct. Claude Benzrihem describes the process of reducing the big political picture down to a more manageable human scale – “I think, in the street, with my neighbour, at home, this is where my fight is – it is the personal quality, my gift. If I can smile to my neighbour then it’s OK – it’s the little things that you can catch. I don’t believe anymore in these big party-political things…There are more little things now that we can be interested in”..

Who gets to bring their values into practice?

Whilst the casual observer may consider bringing values into the workplace as ‘lucky’, this ‘fortunate position’ can be the result of many things – specific experiences, opportunities and exposure to pre-existing studio models. Bejean makes reference to this when reflecting on the earlier period of Labomatic – “The first obvious model we had in mind was Tomato. The fact that they are many people, they are working together and they share an office, money and resources and if one is off, the work can come from the other ones. I wouldn’t think of any other one, we couldn’t be Grapus. We are so not into social issues. They used to work for rich commissioners in order to be able to work for poor commissioners. These kinds of people do not come to us and so we cannot say that we work for them. But we are fighting against the capitalistic society everyday because we suffer from it. We hate that. However we would not refuse to work for a group like Warner because if you do that you just stop working. I am not ready to make that sacrifice. I don’t think it will change things to operate from the inside. I am thinking more about the people at the end of the chain – the people who buy the CD. If one of the 100,000 people has some flash of something, an awareness or questioning, it’s a victory. And that’s how I started, as one of them – looking at the record sleeves and thinking ‘…hmm, this could be done better, or different’. That is the battle I am trying to fight”.

In the instance of Inkahoots the constraints of their values created some problems in their studio’s development – As Robyn McDonald reflected “Our major failing over the years has been lack of marketing – perhaps a hangover from thinking that marketing is a dirty word. I’m way over that. It needn’t be if you do it right, if you’re focused and you are clear about your goals.”

For Paul Elliman’s, this evolutionary process required constant inputs, exposures and references; “My values and beliefs have obviously been also developed for better or for worse through a kind of saturation in art, design, visual languages, literature and their impact on the world. It’s definitely not a a ready-to-wear solution that I would have had when I was younger. I would have found it difficult to imagine how I would proceed as someone who had certain desires and beliefs as a young person. The more obvious logic suggests that I am of a certain socialist tendency and that I am going to go and work for a certain publication that represents that – that’s an obvious political focus. My experience with City Limits, which as I said before, had a stated political agenda, was quite an eye-opener for me because I experienced a lot of middle-class rebellion and selfishness in that particular job. I think I learned something about myself when I worked for that magazine, I began to intuitively formulate ideas about how beliefs and values could be maintained in the work”.

Other practitioners, such as Peter Bilâk, see perpetual learning this as ‘ventilating’ the process of design with continual cultural and intellectual input. This offers the possibility of gauging one’s work in relation to the prevailing cultural environment and reminds us that values are subject to constant change – “To me this was like the story of Jan Tschichold who, being so young and bright, wrote his manifesto that was very influential and when he was older he was the harshest critic of his own work. So he saw that his limit was in his twenties but he lived into his seventies doing some of the most classical work”.

Can anybody bring their values into design practice?

Whereas a ‘manifesto’ infers an evangelical dogma, the bringing of one’s own values into practice is viewed as very much a decision of the individual. Commenting on her experiences of this, Sîan Cook notes “I think it is up to the individual. I don’t think anybody should impose their value systems on anybody else. I think everybody should inform themselves, then they have the information to make the decision – whether to work for client A or whatever. What I really didn’t like about the ‘First Things First Manifesto’ was that after it came out, everybody was trying to score points off each other – ah, well, you signed it but you worked for blah. I thought – no. You don’t know everybody’s personal circumstances, I mean – we all have to live don’t we?”. This approach avoids self-righteousness. Perhaps this lack of dogma could be attributed to the maturity of the practitioners themselves. After all, a begrudged self-sacrifice to your own values is ultimately counter-productive. Cook adds “It’s a quality of life thing definitely. That’s certainly why I do the pro-bono work I do. Not in a martyred sort of way”. Possibly the most concise description of this choice comes from Tony Credland who noted “I wouldn’t be harsh on anybody who was doing it. I can completely understand why they are doing it and I think it’s an internal passion that you believe in and you want to do and if you’ve got the opportunity to do it then try, experiment”.

Values within practice were seen as so natural that it was impossible for them to imagine not doing it. Tony Credland, went further with this point “You don’t sit in the middle as a graphic designer. If you’re working as a graphic designer and you think that you’re not being political then you’re fooling yourself. Just to work as a graphic designer means you are working for a political system”.

By not practicing one’s own values, design work will instead invested with somebody else’s values. In conventional graphic design, these are usually the values of the client. Dutch educator and designer, Jan Van Toorn, demands a more politically aware and socially engaged value in graphic design – “To begin with, communication designers should understand that a political stand does not express itself in direct political action alone. But also in the way that designers deal with social conditions and cultural conventions, including disciplinary dogmas and norms in regard to viewers and readers”.

the empowerment of value systems

Another influential factor in aligning one’s beliefs with profession is empowerment. Having been involved with publications such as the culture-jamming Adbusters, Jonathan Barnbrook implies that this design knowledge can be gainfully employed “Because you’re connected with graphic design, you’re connected with the way that people send out messages, the way that people twist language, twist media”. Barnbrook adds “An interesting thing about working as a designer in a western society is the need to evolve visual language all the time. That is very much a politically motivated thing – a new visual language has to come along every so often to give the sense of newness”. This constant need for newness, promoting an engineered obsolescence, only helps to reinforce graphic design’s compliance to a consumerist economy.Jason Grant states in Inkahoots’ manifesto-like Public x Private, “We hear designers proclaim that they don’t care about or respect politics. Fair enough, but we don’t need to care about or respect politics to acknowledge that the political processes we are inextricably part of, directly or indirectly shape our reality. There is no such thing as an apolitical stance. Not even for a designer. To ignore this is a very political stance”.

Placing values within practice encourages greater flexibility in the studio structure. One of those is the scale of the business itself. Jonathan Barnbrook remarked “I want freedom, not restriction. Most studios, it’s all about income and overheads. Not here. The whole thing – flashy reception and all that, it’s all a distraction. I don’t think design really needs all that”. Many studios, such as Inkahoots, have taken conscious steps to ensure a structure that supports and protects their values,“If we look at the studio processes, one main point is that we don’t have a hierarchical structure. We don’t have an art director, senior designer, junior designer etc. We all comment on the work, we all critique the work so everybody has their say and is open to constructive criticism. It hasn’t always been that way. Some younger designers have felt threatened by this process I suppose. I feel that there is no place for that insecurity if you want to be a strong designer. We are also all paid the same wage. When I was flirting with my options, one of the factors was a personal one. I’m a parent of a ten-year-old boy and my partner all these years has always supported me with my relatively low wage and I felt it was time I contributed more income to my family. When I pressed on with my partners support, I wanted to keep the same wage as everybody else, but we have made a much greater effort towards financial sustainability and I now have use of a company car. That makes me (now in my early forties) feel like I am achieving what I want to do: working with great people, working with my principles but also contributing a little bit more to my family. So that’s the only thing that has changed.’

One designer who experienced great challenges in aligning values with practice, Tony Credland, sees the formation of a formal studio structure as a threat to one’s values.“That is the reason why I haven’t started up a studio. I have seen this happen to friends. The last thing I would want to do is to lose that independent work. I also know that if I ran my own studio I would want to do it really well which would mean working 24 hours a day to the exclusion of anything else. Friends in Holland who have started up studios have been able to survive on very large cultural institutional jobs, that blur the line between whether it is commerce or not. In London it just wouldn’t work but I think that in another city it could be possible”. This highlights the delicate nature of this balance – attracting enough appropriate commissions for viable practice whilst not being so economically reliant as to threaten the articulation of your own values.

the important role of naivety

Curiously, naivety plays a role in many of the experiences of the interviewees. When Jonathan Barnbrook reflected on establishing his own studio after graduating from college “I think it was about not really thinking about what you were doing, what the ramifications were of deciding to do certain things. Being stupid in a way. Just not worrying. Just doing what you want to do. The worst thing that could happen is that you would go back to what you were doing before”. A ‘blind faith’ in a values-based practice sustaining itself helped others, such as Peter Bilâk; “Even until now, I don’t quite understand how I get projects into the studio. When I finish something, something else comes along. I never search for work. When I started of course the fear was that I would not have enough work because I am unable to actively look for it – I don’t know how. So my thing is that I hope that I will be approached to do something that I want to do, or you do your own things. When I was leaving Studio Dumbar, I was safely leaving with one big project in mind, knowing that when I finish I would have this one big project for half a year to keep me busy. The day I left the studio, the project was cancelled. I thought, ‘Great, now what will I do?’. But instead some other projects emerged and because I was free I could do something else. So there were very little plans, more like a series of chances and accidents. Probably that makes it more interesting as well. The important thing is to not worry too much about it otherwise you get stuck. What you worry about, won’t happen. People are used to the idea that you need to work very hard to achieve something. I believe it should be easy, and until now everything works better than I could ever plan it. Of course there was a lot of time investment into projects, but because I like doing it – it seems effortless. And quite naturally, I have plans for projects, deadlines for books and plans for type design. I remember when I was a student and having this admiration for people who had this clarity of vision, they knew exactly where they were going. Later I started appreciating things, like values, doing things responsibly and projects that make you good. You really don’t care how it is going to look, it’s more important that you get a good feeling from it, it is probably leading you somewhere. Without being too spiritual, I think it is important to be comfortable with your Karma, and take things one at a time. That’s why I don’t understand young designers who have these coffee table biographies, talking about their work. It’s still young. It doesn’t feel like the right time to discuss it because it lacks perspective. If you do something innovative, you don’t know how it is seen from afar. I always believe that my work will always get better [laughter]. What would you do with a book about my own work, should I quit working and retire?”

When describing the formation of Inkahoots, Robyn McDonald said that the current studio model is the result of steady refinement over time – “Inkahoots has been an organic evolution into who we are now. It hasn’t felt like an overly conscious process. I set up a group called Black Banana with friends and it lasted a year and never paid wages, it was just friends coming together. After that I set up Inkahoots with some colleagues and really focussed on making a screen-printing collective work. We were all left-wingers working towards social justice and enabling community access to a means of affordable visual communication. Screen-printing in 1990 was such a medium. The people using these facilities were peace activists, local green groups, unions, artists and community members generally. So that was the beginning, the foundation of Inkahoots – an artist-run collective working towards social justice for the community in a very grassroots way. Coming from that starting point, it hasn’t felt peculiar to be where we are now”. This fragile naivety offers an intriguing element in the evolution of value-integrated design practice – and may suggest a possible remedy to an often ‘over-professionalised’ industry of graphic design.

The profile of the designer and the capacity to bring values into practice creates a curious cause and effect relationship – Is it easier to exercise values if you’re famous and working on prestigious projects or is such notoriety a result of bringing values into practice? Tony Credland argues that individual reputation rewards particular designers with projects through which their values can be expressed. “Well, I read a lot of Jan Van Toorn’s texts where he is talking about facilitating change from within the system and I think fine, that’s ok for a lot of well known graphic designers but it’s not reality for somebody like me. I really don’t have the opportunity to choose the jobs I get, I have to fight for any work that comes my way. When I get a job like New Scientist, I can’t stuff it up by putting in the politics too strongly. Everybody in the office knows my politics, I don’t believe in hiding it, that’s for sure. I’ll lay it on the table and they can take it or leave it. At the end of the day, I can’t bring all this theoretical politics about bringing it into your work because it’s just not possible in those kinds of circumstances, in a weekly magazine that goes very fast. I can’t choose pictures the same way Jan Van Toorn can in a big project that spans months. I really respect that sort of work. I would love to be in that position but I’m not, and doubt if I will be, so I need to find other areas to be a political designer”. Even within the activist community, Credland sees that there is clear benefit to having a high profile. “Gerald Paris Clavel in Paris has done well through all that work with Grapus, the position he is in now means being asked to do decent jobs, and to turn down a few. They have such a reputation, high profile that people come to them specifically for political work and their ideas. In my situation I cannot see this possibility but can still work well at a local level”.

Similar frustrations are not uncommon in younger designers, particularly students. Sîan Cook recalls an experience with one of her design students at the Ravensbourne College of Design (UK) “The danger is that students begin to resent the visiting designers who talk about their socially-aware work. It’s that preachy tone that can stimulate that response sometimes – ‘you know, it’s all very well for you to be doing that ethical stuff but I’m in no position to do that”. Yet this argument can also be flipped – that meaningful and powerful work aligned to a value system leads to notoriety. In many cases this study has highlighted that the outcome of highly respected designers being distinctive, critical, even subversive, is because they choose to integrate their own value systems.

different cultures, different approaches

Cultural specificity also plays a role in who gets to bring their personal values into design work – in particular the difference between England and Holland. Jan Van Toorn, Dutch designer and educator explains “In Holland we have had tolerance as a form of social control, that’s not contradictory, it goes together. Along with this sense of tolerance is the idea of the common good that you have to support. Not that you produce only for yourself, you take care of the other, of the common good. In the early part of this century there was this tendency everywhere in the world and certainly in Europe … that you should take care of the social situation. That the public institution is there to take care of the common good. So then when you produce stamps, you produce architecture, the furniture, the costumes of the people, it should demonstrate that there is a better world. The world can be better by the products and the way you behave”.

Hague-based designer, Peter Bilâk agrees “Maybe it is a Dutch thing, that you get involved with the project so early on, that you help to define it and then it basically becomes your own thing. Even if I work for cultural institutions, they have some big idea about what they want to do, you don’t receive a brief of anything, it takes much longer than that, it helps to define it, takes some time to find the funding and then at the end I do the work. So it really blurs the boundaries, whether it is a commission or whether it is self-initiated. Basically you put so much of yourself into it, because of the specific climate here you can get lots of funding for culture. So you can invest more time in cultural work. Very often they work with artists who have their projects and you will be a partner in the project. Usually it starts off quite informally and ends up being official, quite a big thing. The idea of graphic design being subsidised is very much promoted. There are so many cultural bodies which support art, culture and design that it is much more easy to exist because you can get funding for things which normally would not exist.”

Although the international design media often portrays the Netherlands as a design utopia, the Dutch Government are nevertheless singular in their support of design. Slovakian-born Bilâk is appreciative of this situation “…That’s one of the reasons why I came here to work rather than staying in either Prague or Slovakia, which sometimes I think would make more sense because there is much more to do there, probably more important work. Here I can indulge myself doing cool things. If I was to work at home (Slovakia), I would be spending my time explaining what I am doing and then have little energy left to actually do some work. I would be justifying every single little thing, you know, why this is important, and here you get this sort of foundation on which you can build something of your own without having to explain what design is about. But of course it is changing, Holland is just as commercial as anywhere else, the market influence is everywhere, the bigger studios are under commercial pressures with market-driven ideas”.

Even the seemingly negative aspects of place can be used to advantage when brining in values. Throughout the tyrannical reign of Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen in Queensland spawned a left-wing revolt, out of which Inkahoots emerged. This fight fuelled the specific values that informed the practice.

a fine balance

Aligning values into everyday practice presents a delicate balance – between the pragmatic (the daily necessity of rent, wages and other overheads) and more idealistic visions of social or political change. Barnbrook explains, “It should be a balance. Some work is done for money – some work is done for free. If the work is worthwhile, then you should have the space to do it. You shouldn’t be just run by economic factors” says Jonathan Barnbrook when asked about this pivotal point. “…There shouldn’t be a disregard to money however. You run a studio, you pay everybody’s wages”. Barnbrook’s practice is not without contradiction – the combination of left-wing politics with his work with large media multinationals – yet this may simply be a necessary and pragmatic response to the expensive realities of practicing in London.

Bringing values into the workplace is not only subject to everyday financial demands but also by larger patterns of economic activity. Sîan Cook observed that economic downturns gave rise to a corresponding reflexiveness in the design community. During periods of studio ‘down-time’, the opportunity is taken to consider the wider picture of practice such as how much (or how little) meaning it brought into their lives. “Recent economics and the downturn of the design trade has a role to play in this. People often have more time to consider things like their value systems. If you are working in a big design firm and then you’re made redundant, you may begin to question the firm where you thought you would work forever, it might make you think about yourself and the meaning of your job”. Jonathan Barnbrook also sees a clear relationship between economics and values in practice. “Good designers will always do some soul-searching as part of the process of their work anyway. If times are bad, sure, you may have more time but then when times are better you should, because you can afford to”. Being involved with design education, Sîan Cook took the economic ramifications even further by suggesting that the high cost of education plays a prohibitive role in graduates introducing values and meaning into their design careers. “There’s certainly a lot more awareness now, it’s quite heartening. People are quite happy to work on socially aware jobs but the trouble with the paying education system now is that students leave university with a huge debt. I have a lot of sympathy for the students these days. They have to often be more concerned about trying to get the debt down and have economic stability than going out and ‘saving the world’. The urge is there, so if they had the option, they would much rather do these more meaningful things. But short of changing the funding system, there’s not much one can do about that”.

Responding to the economic repercussions of his relatively small design output, Paul Elliman has turned the situation into an advantage by enabling his values to broaden, enrich and in some cases, finance his practice “… But then that has led me to find other ways to get by. And these have supported and maybe even extended my thinking. For example through writing or teaching which I see as equal parts of what I do – designing, teaching, writing”.

Ultimately, this study offers an air of optimism. Most of the interviewees found that an involvement in design education has provided an important supportive framework for critical practice – and for such designers as Sîan Cook, Paul Elliman, Peter Bilâk and Jan Van Toorn, this multi-faceted support not only funds but allows an opportunity to influence the direction of future generations of designers in bringing their own value systems into their everyday design practices.

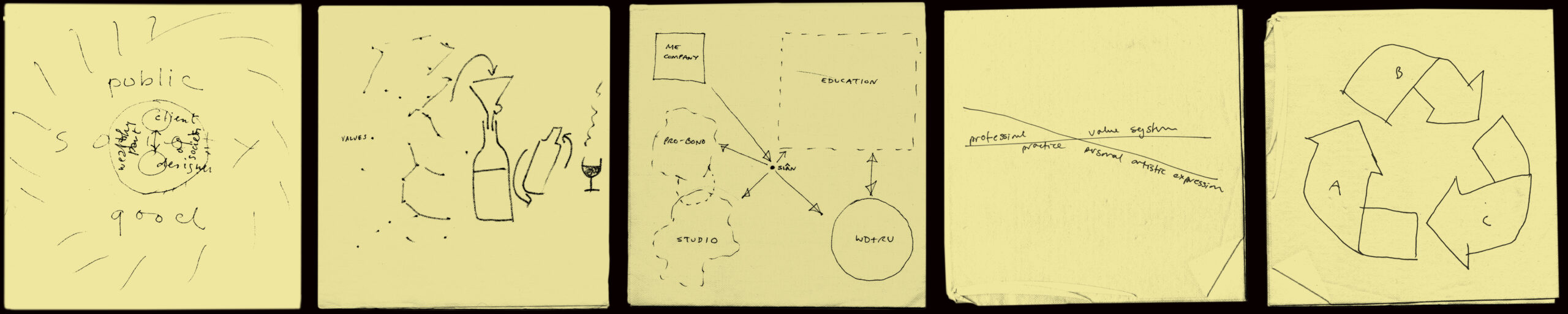

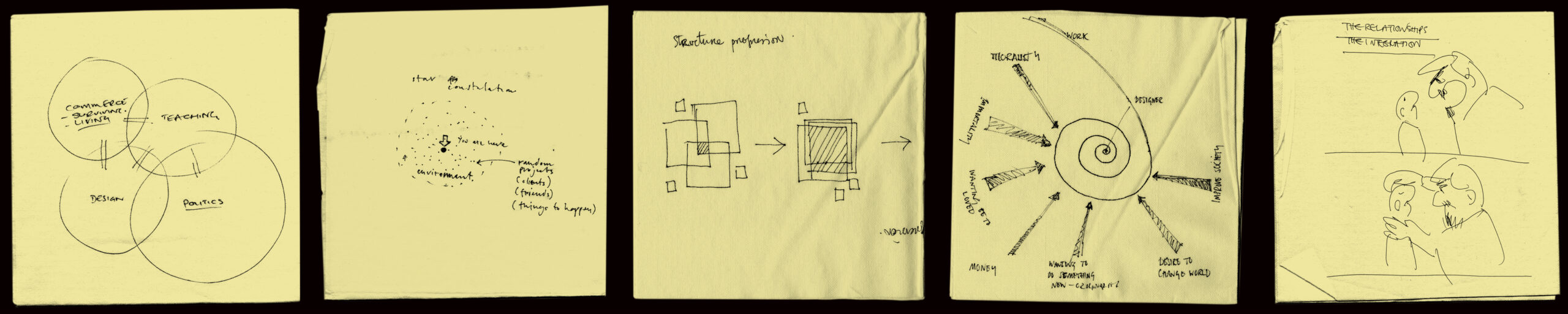

napkin sketches of integrating value systems into practice

This is an edited excerpt from the original research project.